When Serbia defied Yugoslavia: Đinđić’s opposition to Vojislav Koštunica

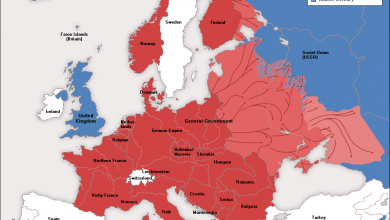

The troubled political landscape of modern-day Serbia is the result of decades of tension, which culminated in the so-called Bulldozer Revolution at the turn of the century. The revolt resulted in the overthrow of Slobodan Milošević’s government, signalling the beginning of a new era for Serbian politics.

However, the wind of change didn’t blow for long. In 2003, barely three years after the process of political reconstruction in Serbia began, Prime Minister Zoran Đinđić was assassinated. When his life came to an end, so did his push for democracy and the rule of law in Serbia. The consequences of this homicide have crippled Serbian institutions to this day, and are still clearly visible in the country’s struggle to obtain positive reform and maintain fundamental constitutional principles.

In between these two events, though, Serbia was the stage for an unprecedented show of defiance against Yugoslavia. The standoff between the Federal Government of Yugoslavia, led by Vojislav Koštunica, and the Serbian government, led by Zoran Đinđić, played a large role in the latter’s assassination. This article will aim to explore how Đinđić tried to stand up to Yugoslavia and the reasons for the souring relationship between these two leaders.

The relationship between Koštunica and Đinđić

Đinđić and Koštunica were no strangers by the time they’d reached the apex of their careers. They had both been prominent members of the Democratic Opposition of Serbia (DOS), a key actor in the Bulldozer Revolution on that fateful 5th of October 2000. DOS was a coalition of very diverse parties, united mainly by their common opposition to Milošević. Within this coalition, two parties stood out from the rest: Đinđić’s Democratic Party (DS) and Koštunica’s Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS).

The former was the oldest, dating from 1990, and it was the first party to openly oppose the communist regime. A split in the party occurred in 1992, with right-wing elements deciding to follow Vojislav Koštunica into the newly formed Democratic Party of Serbia. But with Milošević in power, these two parties still had something in common, regardless of the split: both wanted Milošević out.

On the 5th of October 2000, in the final act of the revolution, Milošević was forced to accept the presidential election results and Koštunica became president of Yugoslavia. From this point on, the two men’s paths would diverge. When Koštunica took office, Milošević’s administration remained in place and the freshly elected President stood by them. On the other hand, Đinđić – who had become Prime Minister of Serbia not much later – sought the renewal of the whole administration, the military, the special forces, and the state media, arresting some of its members if necessary.

Đinđić’s party, the centre-left social-liberal Democratic Party (DS), had no lack of powerful enemies. The fundamental policies of his administration were cooperation with the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), and a relentless fight against organised crime. Unsurprisingly, this made him the target of several groups that longed for the former Yugoslavian dictator Milošević. Said mafia organisations were covered and supported by important elements of Koštunica’s administration, which helped them evade the Serbian government’s attempts to rein in criminal activity.

Koštunica himself had a role in supporting these criminal organisations. He negotiated with the army chief and the head of the special forces during the revolution. All DOS asked of them was their passivity: with the troops remaining by the sidelines, Serbia could spare herself a bloodshed and a new civil war. In return, the two officers, who had both committed crimes during the Yugoslav Wars were to receive immunity by the ensuing federal government. Koštunica would even go on record to say that there would be neither “reprisals” nor “revolutionary justice” against them. This move, in open conflict with DS’s ideals of upholding the rule of law, would drive a wedge between Koštunica and Đinđić, who always opposed granting immunity to henchmen of the regime.

One of Koštunica‘s protégés would be of particular relevance for the succession of events that would follow: Milorad Ulemek, leader of the Special Operations Unit (JSO), a special command of the Yugoslav Secret Services (RDB). He also went by the name of Legija, a reminiscence of his days in the French Foreign Legion, and he would be the one to order Đinđić’s assassination.

The mediatic war to discredit Đinđić

As planned after the 2000 parliamentary election, which had seen Đinđić elected as PM, the Serbian government soon began to chase war criminals located in Serbia. Their first target was the former dictator, Slobodan Milošević, who remained at large until his extradition to The Hague on the 28th of June 2001.

Koštunica’s DSS considered the move was nothing short of treason, due to its historic refusal to cooperate with the ICTY. In July, the party even left Đinđić’s cabinet following a mediatic campaign by the pro-Koštunica media outlets attacking the Serbian government and presenting the prime minister as a corrupted man and a “Puppet of the West”. This mediatic offensive was rooted in the remains of Milošević’s media and intellectuals, now favourable to Koštunica, who were vocal opponent the Serbian government’s project of cooperation with the West.

But the former dictator’s extradition was not the only reason why DSS left the government. The move was also motivated by the assassination of a Yugoslav high-rank security officer who allegedly had evidence of corruption and links between politicians and mafia groups, according to pro-Koštunica media outlets. The prime minister would eventually become the target of ill-founded accusations of being behind this assassination. The mediatic war between Đinđić supporters and the DSS-affiliated media outlets that tried to discredit him and to picture him as a mafia boss would rage undeterred from this moment onwards.

This ongoing war of influence was representative of what was happening in the Serbian society at that time. While Koštunica wanted to avoid deep reforms in Serbia and, by extension, Yugoslavia for the sake of stability, people like Đinđić believed that reforms and chasing criminals for a safer country was the way to go for the future. For DS, Đinđić’s party, this also translated into a strong pro-European stance, which had the unfortunate consequence of reinforcing its “puppet” status towards the West.

The JSO mutiny

Despite the ongoing mediatic war, the Serbian government carried on with its job: the democratisation process and the urgent fight against corruption and organised crime in Serbia. This crackdown began to seriously worry some leaders involved in those matters.

In November 2001, Legija, the JSO leader, organised an armed mutiny with his former colleagues on the highway heading to Belgrade. The uprisers asked for the departure of the Serbian home secretary and the head of the Yugoslav Secret Services (RDB), which were part of his ministry, because of their pursuance of war criminals.

The JSO mutiny could have been avoided or stopped if the federal army had been deployed. However, the JSO’s interests were aligned with Koštunica’s and those of the DSS, so the president refused to send in the troops. Đinđić tried to meet half-way: he didn’t sack his home secretary, but he replaced the head of the RDB by two individuals who were favourable to the JSO and Legija.

The mutiny was living proof that there were irreconcilable differences between the Serbian and the federal government. It also showed that Đinđić’s position lacked the strength needed to prevent such events. However, setbacks like this mutiny didn’t prevent the Serbian government from keeping up its hard work inside the country. While the mediatic war was still ongoing, especially when Milošević’s trial began in 2002, attacks depicting Đinđić as a “spy” or a “traitor” showed no sign of stopping. Meanwhile, Koštunica kept trying to portray DSS and himself as the true Serbian patriots.

The danger was that several of the aforementioned institutions were infested by nationalistic groups deeply linked to mafia groups such as the Zemun Clan, a powerful Serbian mafia group favourable to DSS, opposing the attempts to open the country to the European Union. Their power in Serbia was so high that the government itself could not really control them. By turning a blind eye, the Federal Government did not allow a complete purge of the administration, still full of supporters of the former dictator.

“Serbia on the right road”: EU membership

Very aware of the atmosphere around him and the attempts to discredit him, Đinđić was nevertheless able to rely on the support of most European Union Member States – Schröder’s Germany, Chirac’s France, and Blair’s United Kingdom among them.

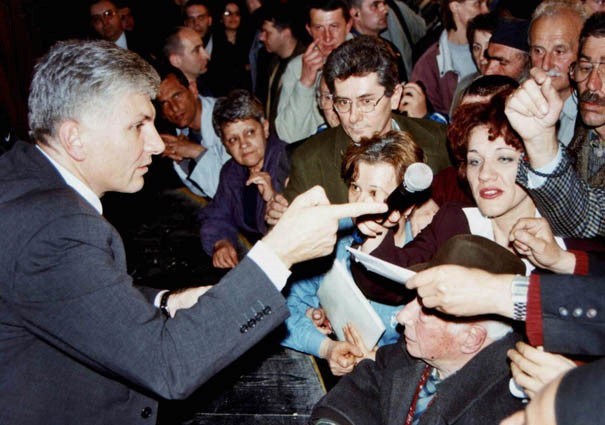

In 2002, the Serbian prime minister began an important campaign in all Serbia, meeting citizens and giving speeches on the future of the country and the great achievements secured so far. His goal was to meet people and to show that his government was working in the best interest of the Serbian people for a better, safer, democratised, and European-integrated Serbia. The campaign name was “Serbia on the right road”.

The campaign goal was twofold: first, he set out to engage directly with the people, bypassing mediatic harassment against him, and second, he sought to win legitimacy beyond his core of supporters, generally the younger generation and the people who had led the Revolution back in October 2000. During all the speeches, he implied that the Serbian government had to fight against destabilization attempts both from the Yugoslav government and the mafia groups which infiltrated the highest spheres of power.

Serbia made some important progress under Đinđić in all matters, despite the attacks committed against him because he represented change, notably in his dedication to cooperating with the ICTY and upholding the rule of law in his country. His views contrasted in a country which, in his own words, “had been kept under water for 50 years”; he wanted Serbia to look upon its future and lean toward democratic ideals, which also meant the complete erasure of any reminiscence of the former dictatorship.

Đinđić’s assassination

The many attempts to circumvent Zoran Đinđić’s policies did not stop him. In his own words, “it’s the final stand. It will be them, or us”. Đinđić really meant it, as the Serbian police launched Operation Sabre on the 13th of March, cracking down hard on mafia groups all over the country. But when Zoran Đinđić gave the green light to this operation, little did he know that it would be his undoing.

His fight against corruption and organised crime was met with relentless harassment coming from media opposing outlets. It soon became evident that many people would be better without Đinđić in charge of the government, and Operation Sabre was the last straw. JSO tried to take him down, the two most notable failed attempts being a rocket fired at his car and an attempt to ram the prime minister’s car on the motorway. They would eventually succeed at killing him on the 12th of March 2003, when Đinđić was shot dead in the back. The bullet came from Zvezdan Jovanovic, a sniper affiliated to JSO.

Eventually, some of the perpetrators of this crime were arrested. Milorad Ulemek surrendered one year after the attack to be given a 120-year sentence. Zvezdan Jovanović was arrested as well and remains in prison to this day. However, the trial was not as straightforward as one would desire, as meddling attempts from government officials were frequent.

Notably, some amongst Đinđić’s supporters accused Vojislav Koštunica’s DSS of being behind the assassination. The theory was that their connections with the JSO and therefore with the Zemun Clan made such an act in their interest. However, Koštunica never did confront the accusations upfront, and it remains an unattested avenue of investigation.

The aftermath

Be it as it may, Zoran Đinđić’s death let back in the very corruption that his government had been fighting against. His fight against corruption precipitated his death, which produced severe changes in Serbian politics in its aftermath. It teaches the lesson that things such as reformism and dedication can be so fragile that may depend on an individual’s willingness to push for them, as it was the case that no one could carry out Đinđić’s reforms after his magnicide.

While Đinđić’s legacy lives to this day, it keeps being attacked by his detractors, trying to go back in his reforms. For the best and the worst, Đinđić’s bequest remains central to Serbian politics nowadays. The current SNS-led government pays lip service to his aspirations, carrying Serbia in quite the opposite direction. It portrays itself as Europhile, but is only so on paper, not disguising its nationalist tendencies well, and it is leading the country with Milošević-like methods.

However, there is a glimmer of hope, for there remains a core of people whose aim is to take Serbia down the road of stability and democratisation despite the many challenges, including harassment. Our hope is that more people will commit to Đinđić’s dream in the near future.