The Ode To Joy: Five Key Facts About Our Common Anthem

The Ode to Joy was adopted by the Council of Europe as its anthem in 1972. Thirteen years later, in 1985, it became the official anthem of the European Community, and of its successor, the European Union.

But what exactly is the Ode to Joy? These are five key facts about Beethoven’s masterpiece.

First of all, naturally, it’s a famous musical piece: the tune is the prelude to the fourth – and final – movement of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9, first performed in Vienna in 1824. It’s a tune about peace: Ode to Joy represents the triumph of universal brotherhood against war and desperation. Indeed, Beethoven himself put to music a poem that praises and wishes for freedom and peace between all peoples.

Secondly, it’s the European anthem. When the Council of Europe decided to adopt it, though, it opted not to include the original lyrics, to avoid privileging a single European language, German, to the detriment of all others. Nevertheless, there are several unofficial adaptations in different languages; in particular the Latin and Esperanto version aim to overcome the limits of national borders.

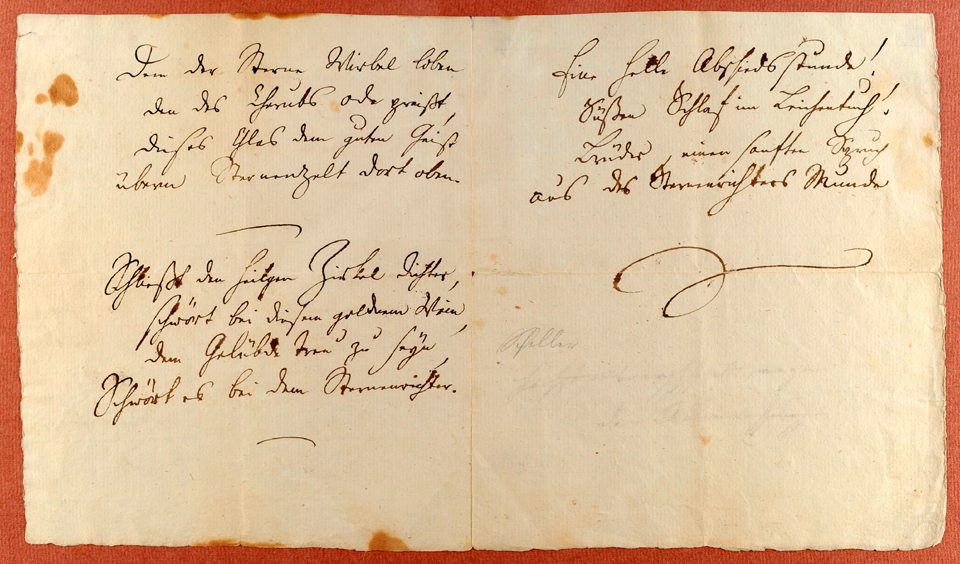

Thirdly, “Ode to Joy” is also a poem written by Friedrich Schiller in 1785, whose original title is An die Freude (“To Joy” in German). Beethoven actually used a posthumous revised version for writing his lyrics. Funnily enough, even if the text was and still is well known and beloved by many, in later life Schiller expressed contempt for his work and dismissed it as typical «bad taste of the age».

The fact that Beethoven chose a text authored by Schiller isn’t a coincidence: the composer was indeed an admirer of the latter’s work as a philosopher. Beethoven is usually remembered for his musical work, but what is less known about him is that he was a fervent idealist. Together with Schiller, the other main authors who influenced Beethoven are Johann Wolfgang von Goethe and Immanuel Kant.

Young Ludwig fell in love with the ideals of a higher morality, the sacredness of duty, and the conception of humans as free and rational individuals. It can be said that Symphony No. 9’s Ode to Joy fully reflects its composer’s mindset.

Symphony No. 9 is also Beethoven’s last finished symphony, and it’s substantially different from the eight that preceded it. All previous symphonies are characterized by a contrast between two main themes, which usually portray two different forces. It can be said that the composer put a piece of himself in his work: Beethoven struggled between opposites throughout his life, balancing creative independence against financial stability, or higher ideals against natural impulsiveness (did you know he changed more than 60 accommodations during the 35 years he lived in Vienna?).

Symphony No. 9, though, was written later in life. At that time Beethoven was completely deaf and had gone through self-isolation, depression and suicidal thoughts. He eventually overcame his despair, but he was deeply changed by it. It is no coincidence then that his most mature symphony doesn’t follow his typical pattern of a clash between two themes, rather a dialogue between several themes and voices.

Curiously, we can see a metaphor for the European Union in this. After the horrors Europeans visited upon themselves during the wars, especially WWII, finally the nations of the Continent stopped fighting each other, opening the way to dialogue. We don’t know if the origins of Symphony No. 9 contributed to the choice of the Ode to Joy as the European anthem, but they surely adds a surprising layer of depth and relevance.

Finally, it’s peculiar that the Ode to Joy movement marks the first time a famous composer used voices in a symphony. It was by all means an innovation for the era, but the critics of the time weren’t so favourable. Among others, Italian opera composer Giuseppe Verdi complained about the vocals in a letter to patron Clara Maffei, writing the symphony was «marvelous in its first three movements, very badly set in the last. No one will ever surpass the sublimity of the first movement, but it will be an easy task to write as badly for voices as is done in the last movement».

Nonetheless, the Ode to Joy, together with the entirety of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9 became part of the UNESCO world cultural heritage in 2003. And by all metrics, it’s a great anthem for Europeans to have: we shall sing it proudly, since Europeans can finally live as brothers and sisters, as Beethoven wished.

I am proud to be a longtime resident of Heiligenstadt, in Vienna, a short walking distance to where the great composer, Ludwig van Beethoven, whose 250th anniversary we are celebrating, lived in the Probusgasse, where he composed, and later, wrote the famous Heiligenstadt Testament.