The Franco-German Recovery Fund Could Change the EU Forever

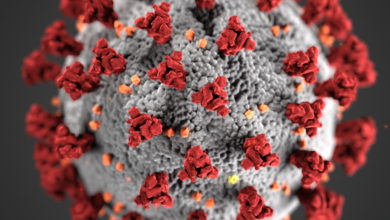

The coronavirus pandemic is a lethal threat to many lives, and has already claimed over 320,000 lives worldwide at the time of writing. But it’s a social and economic challenge as well, and one of terrible magnitude. The recession caused by COVID-19 will be the worst since the Great Depression of 1929. The European Union has been hit hard by the pandemic, with the critical deficiencies in Member States’ leadership laid bare for all the world to see. Berlin and Paris have decided to respond to this leadership vacuum, with a bold proposal for a recovery fund. Should this proposal go through, it might well change the EU forever – and set it on a path towards a real federation.

Eurobonds By Any Other Name

The current EU budget has a very restricted ceiling: it’s capped at 1% of the EU’s GDP. This puts severe limits on how effective, bold, and ambitious the EU can be with its policies even at the best of times – and a global pandemic is far from that.

This is where the Franco-German proposal comes in. In a surprising break from past timidity, France and Germany have proposed an increase for the EU budgetary ceiling for the next three years – raising it to 2% of GDP. That extra 1% would amount to some 165 billion Euros a year, for a total of 500 billion. Crucially, it would not be covered by Member State annual contributions: it would be debt, which the EU can issue in its own name.

This is critical in a number of ways. First and foremost, it means that this new debt would not show up in Member States’ national accounts. This would massively help Member States with low credit ratings and intractable debt problems, such as Italy. Secondly, it builds on a mechanism the EU can already use. Brussels is already allowed to issue debt, but for very limited purposes – typically, to support Member States with economic difficulties or to intervene on the balance of payments. What would change with the introduction of the Recovery Fund is that the sums of debt the EU is allowed to issue would be much larger.

Most fundamentally, this gives the European Commission a political backing and mandate it desperately needed to act. The issue of economic reconstruction is now being reframed as a European problem, not one restricted to the national economies. Technicalities still need outlining: we don’t know how new EU debt will be distributed among Member States, how reimbursing will work out in practice, and whether the system will become a permanent feature of EU policy-making after its expiration, three years from now. But the political commitment is serious. The word “Eurobond” was never mentioned in Franco-German press releases. Ultimately, however, that is what’s at stake right now – and the EU’s financial solidity with it.

The Bad News

It is, perhaps, depressing that this proposal is coming from the two largest Member States in the EU. But this should not surprise us, nor overly concern us. It’s no surprise, because the bitter truth is that the EU is still a low-trust political environment that Member States will only countenance so long as they feel they are in charge. The system can only truly be altered by them, by design. However, some of the claims made in the public debate – that Germany and France are going behind the Commission’s back, for instance – are wildly exaggerated. The Commission strongly endorses the initiative, and was kept informed of its development at all times, as were other Member States.

Claims that this is an undemocratic decision process are also off the mark. In order to become policy, the Fund will need approval from the parliaments of every Member State in the European Union. Naturally, the truly ideal option would be to give the European Parliament the final word. That scenario remains remote, at present. But that doesn’t mean that France and Germany have hijacked European decision-making.

The bad news is that several remain opposed to this scheme. Austria, the Netherlands, and Finland have already voiced their opposition. While Macron and Merkel were telling the press that France and Germany were standing up for Europe and that extraordinary times required extraordinary measures, Austrian chancellor Kurz took to Twitter to dampen enthusiasm for the move. The Visegrad countries have not shown their hands yet. It’s likely that they can be convinced to support the move. What price they will demand remains an open question.

There is a further element of uncertainty: what is going to guarantee repayment? The answer is vital, because the EU having solid credit and market confidence is fundamental for this plan to succeed. Since the Recovery Fund is not part of the Treaties, debt will require purely political backing. The EU needs to make credible commitments to debt servicing and its own financial soundness. This is certainly doable, but it does make the European credit position more volatile with an eye to the future.

The Good News

The need for unanimous approval on the part of the Member States is politically cumbersome, but it also solves a legal problem. The German constitutional court will not have jurisdiction over EU fiscal policy that is cleared by the German parliament (along with its other 26 equivalents in the EU).

The best news of all, perhaps, is that France and Germany are taking the EU seriously again. There is perhaps some reason to hope that the lessons imparted by the 2012 Euro debt crisis did not go unheeded. Paris and Berlin have both recognised the gravity of the situation and the necessity to take the initiative. The ability for the EU to issue its own debt in large scale is a transformative event.

Henrik Henderlein, an economist who serves as director to the Jacques Delors Centre, has labelled this the European Union’s “Hamiltonian moment”, a political signal that “the EU is more than a grouping of nation-states, and has its own federal identity.” Should the Recovery Fund become policy, it might be the EU’s real, first step towards statehood. It will be up to Member States to make that happen. Now more than ever, we need national capitals to rise up to the challenge, be brave – and take the plunge.