The Other Side of Europe: Moldova

‘The Other Side of Europe’ is an article series providing information about the EU’s neighbouring countries located between Eastern Europe and the Caucasus. It follows a series in which we explored opportunities for future enlargement. In this fourth instalment, we will look at Moldova.

Geography and Culture of Moldova

Moldova is an Eastern-European country. It spans across 33,846 square kilometres, sharing its borders on the west and southwest with Romania (separated by the Prut river). To the north, south, and east it borders Ukraine (separated by the Nistru river). Its population amounts to 2,681,735 inhabitants, mainly concentrated in the capital city, Chișinău. Sometimes, especially in Romania and Bulgaria, people refer to the Moldavian people as Bessarabians, from the ancient name of the area (Bessarabia).

The culture of Moldova is indebted to the Byzantine, Magyar, Slavic and Gagauz-Turkish minorities. However, from the second century A.D., after the Roman colonisation of Dacia, Moldovan culture has been influenced primarily by Romania. During the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, many similarities with Romanian culture were kept hidden by the Soviet authorities. For example, the traditional Romanian moccasin (called opinca), which is part of the national folk costume, was replaced by the Russian boot. Nevertheless, Moldovan culture is still closely linked with Romanian culture. For example, many Moldovans like Alexandru Donici, Constantin Stere, and Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu contributed to the formation of modern Romanian culture. Another essential part of Moldovan culture are ancient folk ballads, called Miorita or Meşterul Manole. Some other very ancient traditions live on in the rural areas of Moldova, like ceramics, weavings, and folk choirs, Doina, which is even promoted at the national level.

Similarly, traditional Moldovan cuisine is a mix of several cultures, with Romania again being the main influence. The most famous Moldovan dish is probably mămăligă (a cornmeal porridge, popular also in Romania). It is a staple similar to polenta, usually served as a side to meat dishes, or with cottage cheese or sour cream. Another important dish is ciorbă. It includes a wide range of soups made with vegetable, fish or meat (in this case called zeamă), soured by bors or lemon juice. Regional traditional dishes include brânză (a brined cheese), ghiveci (goat or lamb stew), and local wines. In regions with large ethnic minorities, you can find Ukrainian and Bessarabian-Bulgarian dishes, such as borscht and mangea.

Society and Religion

According to a 2014 survey, Moldovans are the largest ethnic group, accounting for 75% of the population. To this number, we need to add 7% of the population who identify as Romanian. Other minorities are Ukrainians, Bulgarians, Russians, and Gagauzians. Gagauzians are present mainly in Moldova, Ukraine, Turkey, Russia and Belarus. They have been traditionally called “Turkish speaking Bulgarians”. They are orthodox christians and concentrated in the southern part of Moldova.

Moldovan (basically Romanian) is the native language for 80.2% of the population. The official status of the Gagauzia and Transnistria regions safeguards other local languages like Gagauz, Russian, and Ukrainian. Russian is the native language for 9.4% of people, and it enjoys “language of inter-ethnic communication” status like in many other ex-soviet countries.

The vast majority of Moldovans (more than 90%) identify as orthodox christians. A small minority is protestant. In 2016, during the first round of the presidential elections, the metropolitan bishop Vladimir Cantarean called on church members to vote for Igor Dodon, pro-Russian leader of the Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova.

Economic context of Moldova

Moldovan economy is still developing. Agriculture accounts for about 40% of national GDP. In addition to the production of sunflower seeds, walnuts and apples, the most renowned product is wine, which comes from extensive vineyards in the central and southern regions. Most of the production is for exporting, and many enterprises have been passed down through generations. As for many former Soviet countries, heavy industry used to have a fundamental role in the country’s economy, but collapsed after the socialist period.

Currently, one crucial issue for Moldova is energy. With few natural resources, Moldova imports almost its entire energy supply from Ukraine and Russia. In 2013, there was a project in place for building a new pipeline between Moldova and Romania, but its construction is still early stages. In the meantime, Moldova is part of the EU INOGATE energy programme. The programme covers topics such as energy security, EU internal energy market principles, and sustainable energy development.

Despite its progresses, Moldova is still one of the most impoverished nations in Europe. This is largely due to the lack of effective reforms. The Communist Party of Moldova, which won its first parliamentary elections in March 2005, had internal troubles in pursuing necessary structural reforms, even while maintaining a pro-Western stance. Moreover, the region of Transnistria declared independence as a pro-Russia region, even with no countries recognising it. This has generated a “black hole” of contraband and corruption, which has a negative impact on the national economy.

In terms of trade, the Moldovan Parliament approved the Association Agreement (AA) with the EU in 2014, which includes a Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area. Furthermore, the country has Free Trade Agreements with Azerbaijan, Georgia, Turkey, and it is negotiating an agreement with China.

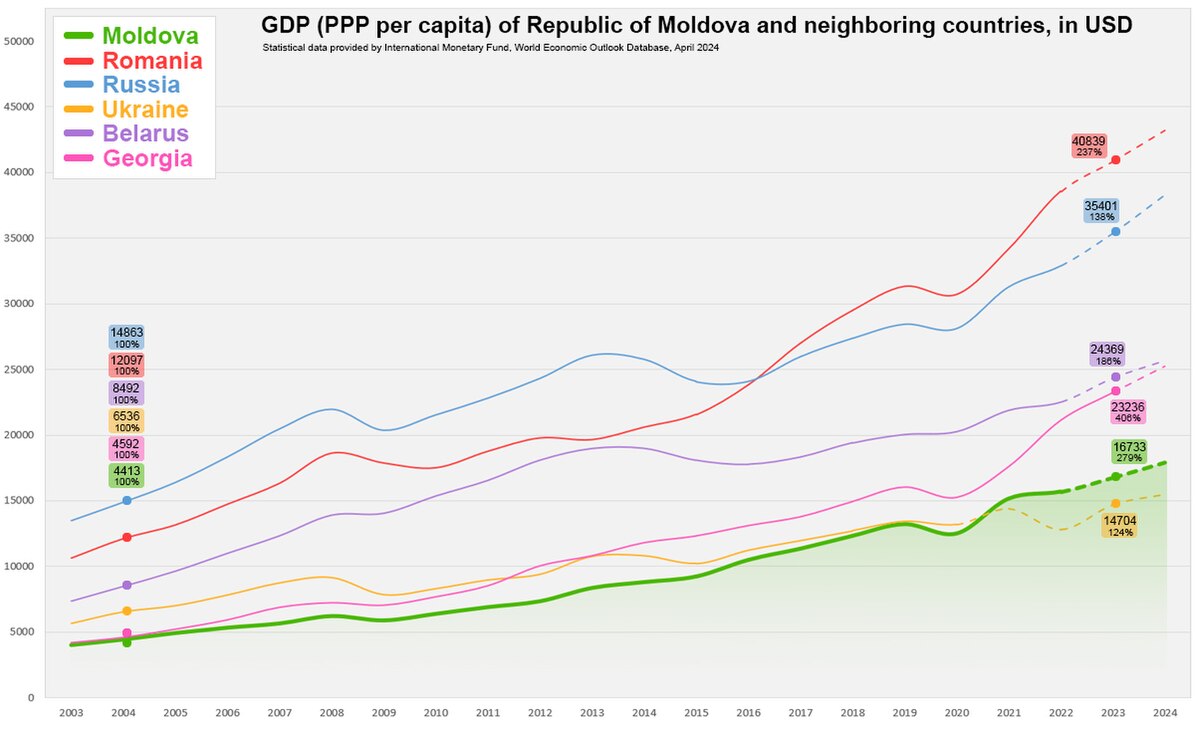

All in all, the Moldovan economy remains highly vulnerable due to many factors. Those include fluctuations in the level of remittances, which can amount to 24% of GDP, as well as changes in the size of exports to the EU and to the Commonwealth of Independent States, which together make up 88% total exports. Currently, GDP per capita is 2.289,88 USD, almost half of the Georgian (4.078,25 USD) and lower even than the Kosovan (3.893,97 USD).

State of relations between Moldova and EU

The European Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) currently governs relation between Moldova and the EU. At the same time, Moldova has a crucial connection with Romania. Between the two World Wars, the countries were united and a not negligible proportion of Moldovans currently identify as Romanian. Moreover, the two people share a common language, culture and flag. The Moldova flag resembles that of Romania, with the addition of the Moldovan national coat of arms. It is not uncommon for some Moldovans to acquire EU citizenship, by way of getting Romanian citizenship on the base of descent.

Currently, the EU is developing a progressively closer relationship with Moldova. Despite a powerful pro-Russia political block, Moldova’s foreign policy is more balanced. After the Vilnius Summit between the EU and its eastern neighbours in 2013 Moldova and Georgia ratified the agreements with the European Union; even though Russia had succeeded in convincing Armenia and Ukraine to halt the Association Agreements with the EU and instead begin negotiations with Russia. Additionally, in 2016, Moldovan President Igor Dodon declared that Crimea should be considered as part of Russia. However, the following year he clarified that Moldova would not officially recognise it, in a bid to maintain relations with Ukraine.

This adds to the issues of Gaugazia, an autonomous region culturally connected to Russia, and of the self-proclaimed state of Transnistria backed by Russia even if not officially recognized. Interestingly, according to a 2018 survey, 46% of the population would prefer for Moldova to join the EU instead of the Eurasian Economic Union (36%).

The Road Ahead

Moldova’s foreign policy is a tricky balance exercise between Russia and the EU. However, this is not sustainable. Sooner rather than later, Moldova will have to make a choice, one that currently would divide the country. Although a stronger connection with Romania and Ukraine could tip the balance in favour of the EU, links with Russia aren’t getting any less strong with time. Ultimately, the future of Moldova appears closely linked to the influence that the EU will be willing to exercise in the region.