Beyond Europe: the International Organisation of the Francophonie

French as an international language: the International Organisation of the Francophonie.

Colonisation brought European languages to prominent roles all over the world, and this cultural legacy persists long after the dissolution of the European overseas empires. As of today, countries, communities and individuals around the world speaking languages such as French, Spanish, Portuguese and English make up the majority of the world’s population.

Another by-product of the cultural and linguistic ties between the home countries and the former colonies is the creation of new international organisations. These tipically favour international cooperation and friendship between countries that share a common language.

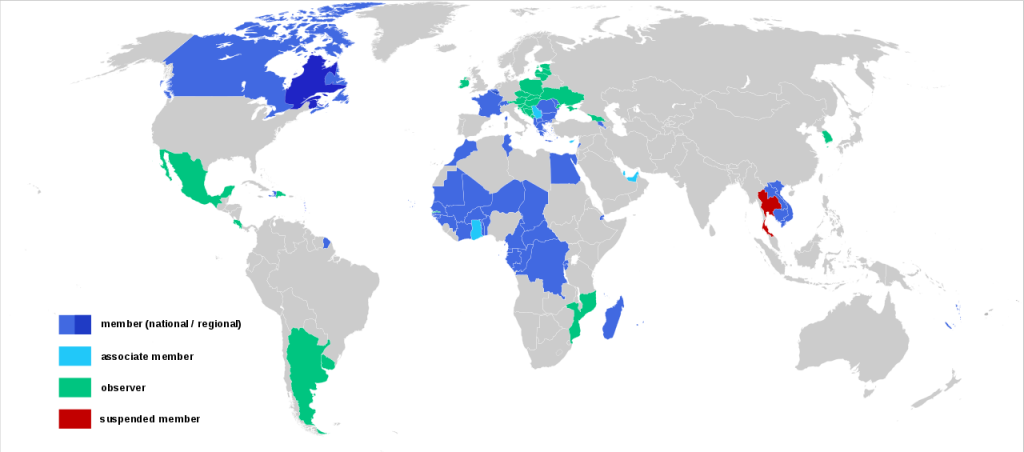

Alongside the Portuguese CPLP, one of the largest among such interngovernmental organisations is the International Organisation of the Francophonie. It accounts over 54 full members, 7 associate members and 27 observers. It was founded in 1970, mainly by the will of African leaders, with the name Agency for Cultural and Technical Cooperation. Since then, the Organisation of the Francophonie has evolved in an articulated organisation comprising different political instances, relying on five operating agencies.

The French language and the world: colonial past, culture and business

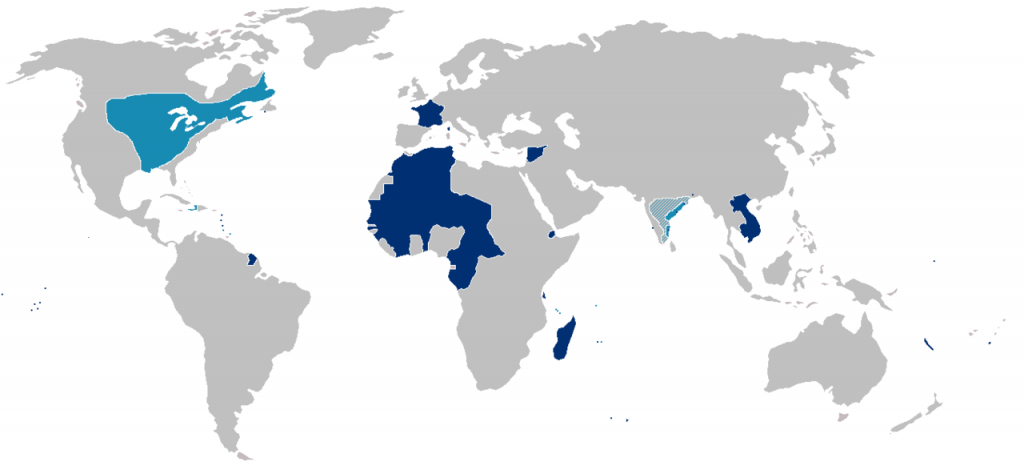

France created a huge colonial empire during the 19th century, after losing its American and Indian territories following the Seven Years War of 1756-1763 against England. That new empire occupied a large portion of Africa, especially Western and Northern Africa, Madagascar, the so-called French Indochina, and other small possessions, mainly archipelagos in the Pacific and the Caribbean (some of which still are part of France), alongside with the only South American territory, Cayenne.

Being France one of the most powerful countries in the world and controlling such an amount of territories throughout three continents and Europe, it was inevitable that its language would have become one of the most important and wide-spoken.

Still, the influence of French literature and arts clearly set a more peaceful way for French to spread. It was widely spoken as a second language and even though the role of France became somewhat less relevant than it were before after World War I and II, French maintained its status as an international language. We can still see some of that influence today, for example in the fact that it’s the only official language of the United Nations Secretariat alongside English.

After the decolonization process ended, French became an official language in most of the newborn countries or kept an unofficial role as a second or business language. Also the former Belgian possessions of nowadays D.R. of Congo, Rwanda and Burundi recognize French as an official language, being Belgium a largely French speaking country.

As of today, French is an official language in 29 countries, nearly 300 million people are capable of expressing themselves in French, and 90 million of these are native speakers. In Europe, over 24 million people are able to speak French in Italy, Germany and the UK alone. One sure thing is that most of those 300 million people live in Africa and the demographic growth of sub-Saharan countries, which means that these numbers will grow fast. In entertaining economic, cultural and political relations with those countries, non-French speaking people could find it useful to learn it.

The International Organisation of the Francophonie

The two main missions of the Organisation of the Francophonie are to promote French as an international language in a time when English seems more dominant and to protect linguistic and cultural diversity. To a lesser extent, it also supports scholarships and higher education, cooperation for sustainable development, and the promotion of peace, democracy and human rights.

The decision-making body of the Francophonie is the Summit – a meeting of heads of French-speaking states and governments, which is convened every two years. This is the core instrument for the implementation of the Organisation’s goals and to discuss topical issues relevant to the French language. There are other four important bodies in the Organisation: an Executive Secretariat, a Ministerial Conference, a Permanent Council, and a Parliamentary Assembly.

There are also five agencies which exist to carry on the Organisation’s missions: the University Agency of the Francophonie (AUF), the Senghor University of Alexandria, the TV5Monde television network, the International Association of French-speaking Mayors (AIMF), and an Assembly gathering the French-speaking civil servants of International Organisations (AFFOI).

Defending French and promoting linguistic diversity: a difficult balance

The general secretary of the Organisation of the Francophonie, Louise Mushiwikabo, said on the 20th of March that she won’t wage “war against other languages”. Such a statement, although quite magniloquent in words, is really important in its meaning. When it comes to linguistic conservation, the risk of taking a dive in the deep dark waters of nationalism is quite high. It’s quite meaningful that the extreme exaltation of national features is named after a French word: chauvinisme.

France has long suffered rivalry with England, and consequently with the English language but the talk about French grandeur is sometimes too influenced by prejudices. After all, the same problems that France has to deal with its own past and the fall of its colonial empire are the same of the UK. Both France and the UK justified colonization as an higher mission to civilize barbarous people, although their respective ideologies differed a lot as well as their outcomes.

It’s still debated to what extent a supposed post-empire syndrome could affect a country, but as of today it seems that globalization is the driving force of reflection on culture, as well as on the meaning of culture as well. The fear for the loss of “culture” is widely spread and we are now witnessing the rise of new and potentially dangerous nationalist parties and politicians across Europe and the so-called Western countries. This new wave of nationalism is trying to embroil language as a mean of exclusion.

In promoting linguistic diversity, the Organisation of the Francophonie seems to be dedicated not to exclusion, but inclusion. However, being it an intergovernmental organisation the risk for nationalistic politicians to interfere with its functioning is high. Also, the perception of organisations such as the OIF as a simple economic tool brings discredit upon them.

Still, to know more than a language is the best way we have to know other people and their culture. Although good feelings alone can nothing, they certainly help, so maybe it’s best to wish luck to organisations promoting ways of reciprocal understanding.