The Next Enlargement Wave: Serbia caught between Russia and Europe

‘The Next Enlargement Wave’ is an article series providing information about the candidate countries for EU membership and their path ahead. In this third installment, we will look at Serbia.

Since the birth of the Coal and Steel Community in 1957, the European project has grown from a meagre 6 founders to its current 28 members through six distinct enlargement waves. Now, the European Union seems to be ready for a seventh wave – this time incorporating the Western Balkans within the bloc. But how does a country go about joining the EU, exactly? It is necessary to meet determinate criteria before even being considered as a potential candidate member. For example, countries must be ‘European‘, something which has proven of difficult interpretation in the past. When Morocco applied, the EU turned it down on the basis that it was not a European country, but only a few years later Cyprus’ application was accepted – even though the island is technically in Asia. Nowadays, it is down to a purely political decision on a holistic basis.

European countries which wish to apply for membership also have to show that they fulfill the so-called Copenhagen criteria. This requires potential candidate countries to demonstrate respect of democracy and fundamental freedoms, the existence of a functioning market economy, and the intent to accept the obligations formed by EU membership. It is only once the Copenhagen criteria are fulfilled that the accession negotiations can finally begin. These negotiations involve the complicated process of adapting the candidate country’s legislation to the EU’s acquis communautaire, the corpus of legislation of the Union.

There are currently five countries which have the official status of candidate countries: Albania, Montenegro, Northern Macedonia (FYROM), Serbia, and Turkey. The European Commission moreover recognises two additional potential candidate countries, which are not ready to start negotiating yet but will probably be in the near future: Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Each of these countries has a unique relationship with the EU, and their negotiating processes has been very different due to the different internal mechanisms. This series will attempt to track the specificities of each of them and what those means for the future of their enlargement negotiations. After looking at Albania and Montenegro, this installment will focus on the Republic of Serbia.

Geography and Culture of Serbia

Serbia is located in the heart of the Balkans, nestled in between Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria, Northern Macedonia (FYROM), Kosovo, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Croatia. It spans across 88.361 sq. km. and has a population of more than 7 million citizens. Due to its geographical position and its history, Serbian culture is a mix of Ottoman, Byzantine and Austrian-Hungarian influences.This can be clearly viewed in the wide variety of typical dishes which can be found here. Serbian cuisine includes elements of different cultures like sauerkraut, moussaka, rakija, handmade beer, and turkish coffee.

Serbian is an official language in Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, and Kosovo, while it is recognized as a minority language in Hungary, Slovakia, Croatia, Northern Macedonia (FYROM), and Romania. It is the only language with a current digraphia including Cyrillic and Latin alphabets, which means that the two are used interchangeably throughout the country. Serbian Cyrillic alphabet was created in 1814 by Vuk Karadžić. Serbia is also very successful in many sports, above all basketball, volleyball, and tennis whose best exponent is Novak Djoković.

Society and Religion

Excluding Kosovo, even though its sovereignty is not recognised by Serbia, the most numerous minorities in the country are Hungarians, Roma, and Bosniaks. These are mainly concentrated in Vojvodina, where Serbians make up only 70% of the population.

According to the Constitution, Serbia is a secular country with religious freedom. The Orthodox Church is the most common religious organisation in the country. Over 84% of the population identifies as Orthodox, including most ethnic Serbians, Montenegrins, Romanians, Macedonians, Bulgarians, and Vlachs. The Roman Catholic Church is spread above all in the region of Vojvodina, while Muslims are primarily present in Raška’s district and among the Bosniaks.

Economic context

The Serbian economy is probably the most successful one in the Western Balkans. It is considered a service-based upper-middle income economy and the tertiary sector is definitely the most important one. In fact, it accounts for two thirds of the total GDP. Other strong sectors are automotive industry, energy, and mining (above all in the south). The export is sustained by iron and steel factories, agriculture, weapons and ammunition, and cars. Its main trading partners are Russia, China, Germany, and Italy together with the other Balkan countries.

The nominal GDP in 2017 amounted $5,599 per capita and $39.366 billion generally. Nominal GDP of other candidate countries like Albania and Northern Macedonia amounted $13 and $11 billion respectively, while the Croatian one amounted $54,840. This comparison is emblematic of the state of the Serbian economy. The Government’s reform program focused on financial stability and living standards. Economic growth is forecast to increase to 3.5% in 2018 (the projection amounted to 3%). Above all the growth of 26.4% of the construction sector was definitely encouraging. Regarding the labor market, the unemployment rate declined from 13.5% in 2017 to 11.9% in 2018 and the average salaries rose by 4.2% in real terms in the first half of 2018.

State of talks and accession chapters

The process to Serbia becoming an official candidate State to join the EU has been very troubled, due to a sequence of unfortunately timed political crises involving first Montenegro and then Kosovo. Technically, the Serbian enlargement project started with the negotiations for a Stabilisation and Association Agreement in 2005, while the country was still federated with Montenegro. At the time, separate technical negotiations were conducted regarding issues of sub-state organizational competency between the two entities in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. However, not that long after Montenegro held a referendum and achieved independence, putting a halt to that particular avenue of conjoined accession. Serbia soon resumed its bid alone in 2007, with negotiations for the agreement being concluded a mere few months later, in April 2008.

This coincided with the declaration of independence of Kosovo, leading to a temporary political crisis within the Serbian government that distracted from the EU accession goals, especially as most Member States quickly recognised the region as an independent country. Moreover, the Netherlands and Belgium refused to sign the Association Agreement, due to Serbia not fully cooperating with the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Because of the EU’s unanimity policy in the area of enlargement, these two vetoes effectively blocked the whole Stabilisation Agreement from entering into effect. The vetoes would only be removed in 2013.

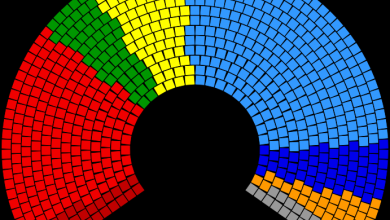

Not deterred, Serbia applied for EU membership in 2009 and at the same time implemented the Stabilisation and Association Agreement unilaterally. It would however have to wait until 2012 before the EU accepted it as an official candidate country. From that moment, it moved swiftly through the acquis chapters. As of now, out of a total of 35 negotiation chapters, 14 chapters have now been opened for negotiations – of which 2 chapters have already been provisionally closed. The latest reports show much improvement in meeting the requirements, especially in the areas of Environment and Agriculture. However, many issues still remain critical and progress is needed in the areas of Financial & Budgetary Provisions.

The Road Ahead

One of the most pressing issue for the future of EU-Serbian relations is the rapidly-decreasing support for accession. From a 2017 survey, in fact, only 51.2% of the population was in favour of joining the EU, 36.3% were against and 12.5% undecided. In 2009, right after the Stabilisation Agreement unilaterally entered into effect and the Serbian government submitted an official request to become a candidate country, support for accession was arond 71%. Other than a generic sense of discouragement and resentment due to the long waiting times of the negotiations, there have been two main political devolopments which have contributed to this dwindling: one related to EU-Kosovo relations and the other to Serbia-Russia relations.

It is impossible to consider Serbian accession to the European Union independently of the Kosovo situation. Even though the Belgrade government made huge progress in the dialogue with Prishtina, public opinion about this issue is still very conflicted. As it stands, there doesn’t seem to be any significant opening towards official recognition of the breakaway region. From the same 2017 survey, another question asked: “if recognizing the independence of Kosovo were a condition of joining the EU, do you think that condition should be accepted?“. Only 12.1% answered yes, 70.6% no and 17.3% were undecided.

Another problem – equally if not more pressing, but often forgotten – arises from the strong relationship between Serbia and Russia. Even though the current government is trying to adopt a balanced approach and mediating between Moscow and Brussels, Russia still remains the main political partner of Serbia. Moreover, in 2015, Serbia started negotiations for a free trade agreement with the Russia-headed Eurasian Economic Union, strengthening its ties with the east to the detriment of its relations with the west. This can contrast with the interests and the defensive expectations of eastern EU countries like the Baltics, Poland, Finland, and Sweden. As a result, it is probable that the EU will require a political and economic detatchment from Russia before the negotiations are allowed to progress significantly – something Serbia may not be ready to offer.