The Next Enlargement Wave: Turkey Keeps Losing More Ground

‘The Next Enlargement Wave’ is an article series providing information about the candidate countries for EU membership and their path ahead. In this fourth installment, we will look at Turkey.

Since the birth of the Coal and Steel Community in 1952, the European project has grown from a meagre 6 founders to its current 28 members through six distinct enlargement waves. Now, the European Union seems to be ready for a seventh wave – this time incorporating the Western Balkans within the bloc. But how does a country go about joining the EU, exactly?

It is necessary to meet determinate criteria before even being considered as a potential candidate member. For example, countries must be ‘European‘, something which has proven of difficult interpretation in the past. When Morocco applied, the EU turned it down on the basis that it was not a European country, but only a few years later Cyprus’ application was accepted – even though the island is technically in Asia. Nowadays, it is down to a purely political decision on a holistic basis.

European countries which wish to apply for membership also have to show that they fulfill the so-called Copenhagen criteria. This requires potential candidate countries to demonstrate respect of democracy and fundamental freedoms, the existence of a functioning market economy, and the intent to accept the obligations formed by EU membership. It is only once the Copenhagen criteria are fulfilled that the accession negotiations can finally begin. These negotiations involve the complicated process of adapting the candidate country’s legislation to the EU’s acquis communautaire, the corpus of legislation of the Union.

There are currently five countries which have the official status of candidate countries: Albania, Montenegro, Northern Macedonia (FYROM), Serbia, and Turkey. The European Commission moreover recognises two additional potential candidate countries, which are not ready to start negotiating yet but will probably be in the near future: Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Each of these countries has a unique relationship with the EU, and their negotiating processes has been very different due to the different internal mechanisms.

This series will attempt to track the specificities of each of them and what those means for the future of their enlargement negotiations. After looking at Albania, Montenegro,Serbia and Northern Macedonia (FYROM), this installment will focus on Turkey.

Geography and Culture of Turkey

Turkey is a transcontinental country, straggling Europe and Asia: the country’s Aegean Region, and the western half of Istanbul, are geographically in Europe, whereas the entirety of Anatolia is located in Western Asia. Turkey borders Greece and Bulgaria to the northwest; Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Iran to the east; and Syria, and Iraq to the south. The country has a total area of 783,356 sq. km. with a population of 80,810,525 citizens.

Turkey has retained the rich cultural diversity of its predecessor, the Ottoman Empire. The latter was a mix of Greco-Roman and Islamic influences, and present-day Turkish culture is a melting pot in its own right, with influences from all over the Mediterranean, the Middle East and Central Asia.

Turkey is currently home to many ancient languages, like Hittite, the earliest Indo-European language of which we have written evidence. Distinctly from the Ottomans, modern Turkey has also been shaped by the Westernisation brought about by Mustafa Kemal “Atatürk”. The republic’s official language is Turkish, which is spoken by 85.54% of the population. A sizable minority (11.97% of the population) speaks Kurmanji, a Kurdish dialect, and is concentrated above all in eastern Anatolia. In Turkey’s western provinces, Albanian and Greek feature prominently as minority languages.

Turkish cultural diversity is reflected in its cuisine; widespread in all the former Ottoman territories, it is renowned for kebabs, pilav, and musakka. Turkish coffee is a favourite across the Balkans and in the Maghreb. Sweets like baklava, kadayıf, künefe, and the lokum (also known as Turkish delight) are popular dessert choices in these regions as well.

Turkish cinema is also a regionally vibrant industry, with some international recognition. In 2008, director Nuri Bilge Ceylan won the Best Director Award at the Cannes Film Festival, with the movie Üç Maymu. Another famous Turkish director, above all in Italy, is Ferzan Özpetek, who won the Best Film and Scholars Juri awards at the 2003 David di Donatello Awards, as well as the Crystal Globe and Best Director awards in 2003 with the film La finestra di fronte.

Sports also enjoy a prominent role in Turkish popular culture. Even though the traditional national sport is oiled wrestling (Yağlı güreş), the westernisation of the country also led to the spread of football, which has become the most popular sport in the country. Top teams include Galatasaray, Fenerbahçe and Beşiktaş. Turkey’s national volleyball and, above all, basketball teams are also renowned.

Society and Religion

Much like Turkish culture, Turkish society also sees participation from groups other than Turks. The main minority is without doubt the Kurds, who are the outright majority in several eastern and south-eastern districts of the country. Moreover, people of Albanian ancestry are common all over the country. As a symbol of this co-existence, one of Istanbul’s historic neighbourhoods is called Arnavutköy, a Turkish name translating to Albanian village.

Kurds and Albanians are just two of the many minorities currently living in Turkey. Bosniaks are another example, with communities above all in Istanbul, Ankara, Izmir and Adana. In 2010, Turkish Foreign Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu famously claimed that more Bosniaks lived in Turkey than they did in Bosnia.

Levantines should also be mentioned: these are Italians, above all of Genoese and Venetian ancestry, and in spite of their low population count (coming at about 35,000), they have played an influential role in Turkish history. Their influence is still visible in architecture, most famously with the construction of the Galata Tower in the former Genoese district of Istanbul. Levantines still live in the districts of Galata, Beyoğlu, and Nişantaşı, as well as in the city of İzmir.

Other ethnic groups include Bulgarians, Greeks (above all near the border with Greece), Germans or Turkish-Germans, and Central Asian peoples like Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and Turkmen. In terms of religion, 98% of the population is Muslim (80.5% Sunni, 16.5% Alevis and 1% Quranist), with 0.5% of Jews, and 0.2% Christians. The latter two are especially popular among minorities.

Economic context

Turkey has the world’s 13th largest GDP by PPP, and 17th largest nominal GDP, with a diversified national economy. The country benefits from a sizeable automotive sector: in 2015, Turkey produced over 1.3 million vehicles in 2015, ranking as the 14th largest motor vehicles manufacturer in the world. Likewise, the manufacturing of electronics is an important sector, with Beko and Vestal ranking among the most important European producers of consumer electronics.

Another fundamental sector for the Turkish economy is energy. In 2008, 7.555 km of natural gas pipelines and 3.636 km of petroleum pipelines ran across the country – and that was before the construction boom that began in recent years. The famous Trans-Adriatic Pipeline passes through Turkey as well, with the government additionally negotiating the construction of the new Turkish Stream.

The transport sector is similarly well developed, the airline industry in particular. Turkey counts 98 airports, 22 of which are international. A new international air hub is currently under construction in Istanbul, and it is planned to be the largest airport in the world, with a capacity of 150 million passengers per year. It would be the metropolis’ third airport, in addition to Istanbul Atatürk and Istanbul Sabiha Gökçen Airport. Turkish Airlines was the biggest carrier in the world by number of countries serviced in 2016. Tourism has skyrocketed over the course of the last twenty years, and seventeen UNESCO World Heritage Sites are located in Turkey.

Nevertheless, Turkey has been hard-hit by the Great Recession in 2008, and has suffered further economic upheavals since then. The last six months of 2018 have seen high market volatility, and a dangerous depreciation of the lira – tumbling to 50% lower than in early 2018.

In this light, growth forecasts have been slashed: Turkey grew by 7.4% in 2017, and by 3.7% in 2018. The slowdown is not over: growth is predicted to go down to 2.3% in 2019. The political uncertainty and, above all, risky foreign policy context is also proving a deterrent to foreign direct investments. Poverty is still expected to decrease: it was 9.3% in 2017, and 9% at the end of 2018. It is forecast to go down to 8.8% in 2019.

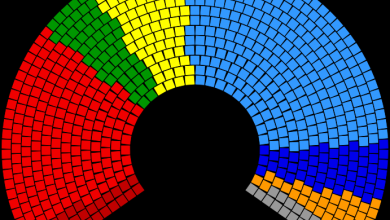

State of talks and accession chapters

Turkey was one of the first countries to become a member of the Council of Europe in 1949. The country signed a Customs Union agreement with the EU in 1995, following its previous application to the European Economic Community in 1987. In 1999, Turkey was officially recognised as a candidate for full membership. The negotiations started in good spirits in 2005, but progress was slow, and the 2008 meltdown, with its subsequent political upheavals, made matters worse. Sixteen chapters have been opened (and one closed in May 2016), out of the necessary thirty-five.

In 2016, Turkey and the EU negotiated a deal on the management of the refugee crisis, in which the former agreed to host large numbers of Syrian refugees. In the intentions of the government in Ankara, this should have accelerated the granting of concessions on visa-free travel throughout Europe for Turks. At time of writing, however, there has been no progress on that front.

The slowdown, if anything, has morphed into a near-total halt in 2016 and, above all, after the failed coup d’etat. The EU has accused Turkey of human rights violations, and EU officials have expressed the very clear view that Turkish policies in response to the coup are in violation of the Copenhagen criteria for accession.

The most problematic chapters currently being discussed are Freedom of Movement For Workers, Fisheries, and Judiciary & Fundamental Rights. In addition to these, fourteen unopened chapters have been frozen. It is important to underline that a further obstacle to Turkish membership is continued opposition, for over a decade, by Member States who do not consider Turkey as a European country. The promised opening of five further chapters has been delayed indefinitely after the refugee crisis.

The question of the response to the coup looms over every negotiation: many academics and journalists have been imprisoned after the failed coup d’etat, and the conditions of their detention, as well as the conduct of the trials themselves, have been criticized by human rights organizations and by the EU. In 2018, the EU’s General Affairs Council stated that: “The Council notes that Turkey has been moving further away from the European Union. Turkey’s accession negotiations have therefore effectively come to a standstill and no further chapters can be considered for opening or closing and no further work towards the modernisation of the EU-Turkey Customs Union is foreseen”.

During her latest meeting with the Turkish Foreign Affairs Minister, Mevlut Cavusoğlu, Federica Mogherini added that “We expressed our strong concerns about the detention of several prominent academics and civil society representatives, including those recently detained”. Nevertheless, the negotiations for full membership are still open and the meetings go on.

The Road Ahead

Turkey still has a long road ahead towards full membership of the European Union, and it’s hard to make predictions about whether further progress will be made, and if so, when. The geographical position of Turkey is strategically significant, but also implies difficulties, as Turkey borders current hot zones in the Caucasus and the Middle East, where it has significant security commitments.

Erdoğan’s government is determined to re-establish Turkey as an independent, regional power player, acting as the revolving door between Europe and Asia. To do so, Ankara is making a concerted effort at increasing its clout in the Middle East (through hard power) and in the Balkans (through soft power). This foreign policy doctrine has been labelled as Neo-Ottomanism, and it holds the distinct risk of pushing Turkey even further away from a full EU membership.

Ankara’s complicated, but nevertheless deepening ties with Russia could also create further distance. Other lingering issues remain, such as the increasingly authoritarian post-coup environment, and the question of Northern Cyprus, which is not recognised by any country save for Turkey itself.

These obstacles look problematic in isolation, but once combined, they form a truly formidable roadblock to European accession for Turkey. In addition to that, these issues affect more than just relations between Turkey and European countries, as they come to play roles domestically, like during the recent German elections. This makes the task of European officials to pursue the opening of new chapters, and Turkey’s integration in the European Union, cumulatively harder.