The Next Enlargement Wave: Albania off to a Rocky Start

‘The Next Enlargement Wave’ is an article series providing information about the candidate countries for EU membership and their path ahead. In this first installment, we will look at Albania.

Since the birth of the Coal and Steel Community in 1957, the European project has grown from a meagre 6 founders to its current 28 members through six distinct enlargement waves. Now, the European Union seems to be ready for a seventh wave – this time incorporating the Western Balkans within the bloc. But how does a country go about joining the EU, exactly? It is necessary to meet determinate criteria before even being considered as a potential candidate member. For example, countries must be ‘European‘, something which has proven of difficult interpretation in the past. When Morocco applied, the EU turned it down on the basis that it was not a European country, but only a few years later Cyprus’ application was accepted – even though the island is technically in Asia. Nowadays, it is down to a purely political decision on a holistic basis.

European countries which wish to apply for membership also have to show that they fulfill the so-called Copenhagen criteria. This requires potential candidate countries to demonstrate respect of democracy and fundamental freedoms, the existence of a functioning market economy, and the intent to accept the obligations formed by EU membership. It is only once the Copenhagen criteria are fulfilled that the accession negotiations can finally begin. These negotiations involve the complicated process of adapting the candidate country’s legislation to the EU’s acquis communautaire, the corpus of legislation of the Union.

There are currently five countries which have the official status of candidate countries: Albania, Montenegro, Northern Macedonia (FYROM), Serbia, and Turkey. The European Commission moreover recognises two additional potential candidate countries, which are not ready to start negotiating yet but will probably be in the near future: Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina. Each of these countries has a unique relationship with the EU, and their negotiating processes has been very different due to the different internal mechanisms. This series will attempt to track the specificities of each of them and what those means for the future of their enlargement negotiations.

Geography and Culture of Albania

From its position in south-eastern Europe, Albania spans across 28,748 sq. km. and has a population of around three million people. There are two main linguistic and ethnographic groups dominating the country: the southern Tosks and the northern Ghegs. The line separating them has been identified approximately at the Shkumbin River, which completely divides Albania from east to west. Although ethno-linguistically different, both sides take pride in indisputable loyalty to Albania and to the values of Albanian independence.

The Tosk dialect group is spoken not only in Albania, but also by the ethnic Albanian population in Greece, in southwestern Northern Macedonia and by the arbëreshë in Southern Italy. The Tosks are also linked with a more Southern Mediterranean culture. In particular, the music and the food are very similar to the Greek and Southern Italy ones. On the other hand, Gheg is also spoken by the Albanians of Kosovo, Montenegro, Croatia and northwestern Northern Macedonia. It is usually linked with more traditional Balkan lifestyles and customs.

Society and Religion

Chief among the common values uniting Albania is religious tolerance. This is a famous feature of the country, where Catholics, Muslims and Orthodox Christians have long enjoyed peaceful coexistence. For example, Albania was the only country in Europe where the number of Jews increased significantly during the Nazi Holocaust. Its Muslims are very different from those which could be traditionally found in the Middle East. Albania follows Bektashism, a branch of Islam which uses temples called tekke instead of mosques, and has very liberal approaches to alcohol consumption.

From the end of World War II to the Nineties, Albania faced one of the most terrible Communist regimes in Western Europe, which led the country to almost complete isolation from the rest of the world. Following the collapse Enver Hoxha’s regime, many Albanians have taken to leaving the country and settling in Western European countries in hope of a better future. This has given life to what is considered a fully fledged diaspora, of which the exact numbers are not known. Estimates place the number at around 800 thousand, a considerable amount for such a small country.

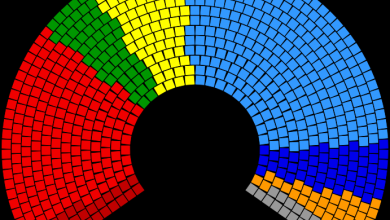

Nowadays, the country has developed three main parties in its political context: the centre-right Democratic Party, the centre-left Socialist Party, and the centrist Socialist Movement of Integration. As of the last elections, Prime Minister Edi Rama from the Socialist Party has the absolute majority in terms of parliamentary representation, and as such govern without any need of coalition.

Economic context

The Albanian economy has been making huge economic progress since the transition from a socialist planned to a free-market economy. Gone are the days of Albania as the poorest nation in Europe – nowadays it has become a middle-income country where poverty is in continuous decline. Nevertheless, there are several still critical elements highlighted by the global financial crisis. Albania needs to carry out deep structural reforms in order to raise productivity and to improve governance and the public services.

Recently, the Government has proposed a program focused on fiscal sustainability and financial stabilization. According to the World Bank reports, this would help in creating the conditions for rebounding business confidence and domestic demand. Albania’s GDP grew by 3.8% in 2017 above all thanks to private investment and consumption, above all linked with the energy projects of the Trans-Adriatic Pipeline.

Private consumption, on the other hand, was supported by a higher rate of employment and credit. Technically, the fiscal policy involved a reduction of public debt, but this rose – even if slightly – from the 1.8% of GDP in 2016 to 2% in 2017. The unemployment has currently decreased to an average of 13.9%. The poverty rate in 2017 has declined to 32.8% compared to 33.9% of 2016. Economic growth is expected to arrange to 3.6% in 2018 and to 3.5% in 2019-20.

State of talks and accession chapters

Although Albania has technically been a full candidate country since 2014, there have yet to be any opened acquis chapters, as the Council of the EU keeps postponing the start of negotiations. Albania’s journey started 18 years ago, having been recognised as a “potential candidate” in 2000. The country had to wait until 2003 to start the negotiations for a Stabilisation and Association Agreement, which weren’t fully completed before another three years. And that was just the beginning of its path: in 2009, it applied for membership, but had to wait until 2014 and the Thessaloniki European Council just to be recognised as a candidate country.

Although most members of the European Parliament and the Commission have repeatedly stated that Albania is ready to progress, the Council of the EU has so far not been convinced. As of right now, it has no chance of progressing in the negotiations until June 2019, when the Council Ministers will meet again to decide whether to give the green lights to the negotiations. The latest reports show much improvement in meeting the pre-accession requirement, but some aspects still remain critical. Huge progress has been made in the areas of Environment and Climate Change, as well as those of Justice, Freedom and Security. However, its Consumer & Health Protection, Science & Research, Fisheries and Agriculture & Rural Development still remain underdeveloped and a priority to improve upon before negotiations may begin. The last aspect is probably the most critical, and is linked with the lack of communications between the city and the countryside, above all in the north of Albania.

The Road Ahead

The biggest obstacle which Albania will face from other EU Member States comes probably from Greece, which it has several unresolved issues with which stem all the way back to World War II. After the Italian occupation forces in Albania attacked Greece in October 1940, Greece passed a law declaring a state of war between the two countries. This law has yet to be repealed, although in 2016 the two Foreign Ministers stated that they were working towards a formal closure of this long forgotten war.

The consequences of this state of war, however, stem further than the formal conflict itself: the fate of the ethnic Albanians who were exiled from Greece during and after the war is still a hot and controversial topic between the two. The Cham community, a sub-group of Albanians, lived in the western part of the region of Epirus in northwestern Greece (which they call Çamëria and believe to be rightfully Albanian land). During that time, The Cham were accused of collaborating with the German occupation and thus expelled from the country as well as being subject to violence. And that’s not all: the maritime borders between the two have also been subject to much scrutiny and conflict in the past few years, and a resolution doesn’t seem forthcoming.

Another important obstacle for the future of Albania’s negotiation is the state of Kosovo. Prime Minister Edi Rama has repeatedly stated that Albania will only join the EU if it can do so together with Kosovo, but this poses several logistical issues. First and foremost, there are still EU countries which do not recognise the break-away Serbian region. Among them, Spain has had huge problems with regional claims above all in Catalunya (in addition to the historical dispute with the Basque country) during the last year, and has been very reticent in recognising Kosovo.

Moreover, Kosovo still hasn’t achieved the status of candidate country and it doesn’t seem likely that it will obtain it in the near future, so it would be extremely tricky in terms of timing to have the two join together. On the other hand, though, allowing Albania in the EU first would pose difficulties in the management of a possible external border with Kosovo, which both countries have been clamouring to abolish for years now.

While resolutions to these issues don’t seem forthcoming, and while the Council remains reticent to allow Albania to progress, it seems unlikely that the goal of having the Western Balkans join the bloc by 2025 will be met.