In the EU Elections, Much More is at Stake Than the Rise of the Far Right

The Far Right is Turning the Elections into a Monologue. We Must Not Let It.

With the EU elections only six weeks away, pundits and pollsters are busily predicting the composition of the coming European Parliament, and so far, it looks like there will be few surprises. The EPP will emerge as the largest party once more, and while S&D is now within reach of ALDE, it is likely to remain second, especially in the event of a British participation to the elections. And what about the far right?

The much feared breakthrough of the so-called populist parties has so far failed to materialise. The parties in question are likely to do better than 2014, but only marginally, climbing from around 20% to 22% of the seats. The EPP and S&D are both hemorraging seats, but liberal and green parties around the Union have reaped at least as many, if not occasionally more benefits from it than right-wing extremists have so far. Of course, you wouldn’t know any of this if you only had the media coverage of the EU elections to go on.

Spotlights In All The Wrong Places

Traditional coverage of the far right is stuck in a feedback loop, in which the latest publicity stunt, food picture, or impromptu selfie by a prominent anti-EU politician gets disproportionate amounts of attention, leading to more stunts, outrageous statements, and so on. Through this perverse mechanism, far right parties make the headlines, dictate the pace and tone of the campaign, and enjoy the media’s veritable obsession with their platforms.

It’s not just traditional media who share this obsession, either. As research conducted by think-tank ISD shows, the far right is much more skilled at creating buzz around itself on the internet, with Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement Nationale in France and the equally far-right Alternative fur Deutschland in Germany operating two out of every five political posts on the EU elections on Facebook. The amount of reactions they garnered is equally high.

These numbers are completely inconsistent with these parties’ polling numbers, and they reflect more than mere skill from the far right’s social media mobilisation. They are also a sign of the communication vacuum that hampers established parties, which are conspicous only for their absence. This allows the far right to effectively set the talking points for the election, focusing on immigration, opposition to LGBT rights, and its own oversized ego. As a result, the much greater stakes of our Union-wide elections take the backseat, or are completely lost.

In the Coming EU Elections, So Much Is At Stake

When campaigning for the 2014 EU elections, Jean-Claude Juncker said that the coming term would represent “the Commission of the last chance”. While this might not have proved literally true, it certainly reflects the spirit of the times. The next European Parliament – and with it the next European Commission – will have to face challenges so tough that they defy description, both abroad and at home. They will have to do so under more intense public scrutiny, while dealing with increasingly fractious, divided Member States.

Enumerating all these challenges would turn this article into a shopping list. Nevertheless, even a cursory look reveals just how daunting they are. While the European Single Market is one of the EU’s crowning achievements, for example, some of its fundamental features remain incomplete: the digital single market and the energy union, to name two. Additionally, the economic and monetary union also remain in no man’s land, with divergent ideas on how to move forward, or if we have to move forward at all.

And all this is just scratching the surface. The Great Recession of 2008 has been the single largest transformative event in Western politics since the fall of the Soviet Union. Trump’s threatened imposition of trade tariffs against the EU and China, which might well trigger a global tariff escalation, has already caused a worldwide economic downturn which might lead to a new recession, one which the EU is fundamentally not ready to tackle. Ten years after the Great Recession first erupted, the European economy is crippled by inefficiency, anemic growth, and a seemingly unstoppable decline in individual purchasing power. The European banking sector remains in shambles, and is overshadowed by American and Chinese finance.

Into The Danger Zone

This complicated environment is further aggravated by foreign policy challenges. The European Union is still looking for a way to save the Iran deal, and the ensuing diplomatic row with the United States is threatening the common financial architecture of the Western world. Russia remains aggressive and resurgent to the east, and while sanctions are slowly strangling its capabilities to conduct further acts of aggression, only a continued application of pressures will yield results. Internally and externally, pressure is mounting for the EU to pool its military capabilities and acquire the ability to defend itself.

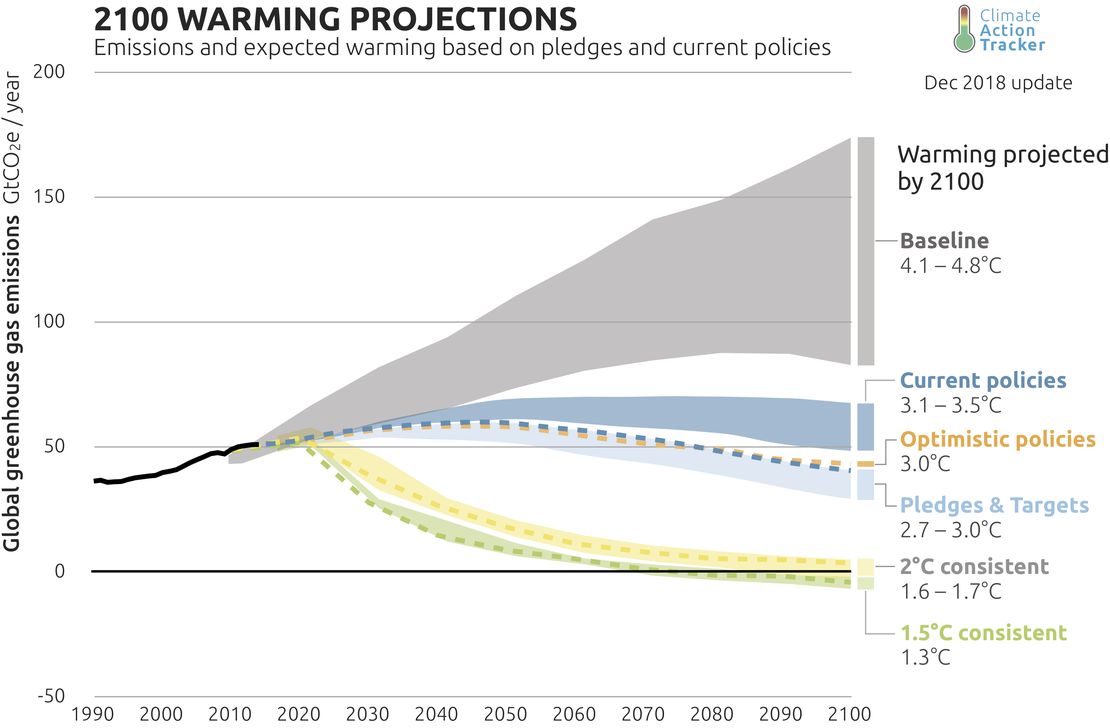

This list would be daunting under the best of circumstances. As if this wasn’t enough, the most ominous piece of the puzzle remains: climate change poses a challenge that overshadows everything listed so far. Even more ominously, with the Paris climate agreement in agony, the new Parliament and Commission ushered in after the EU elections will have to answer some very tough questions about how best to deal with climate change, the one threat besides nuclear war that is actually capable of causing the collapse of civilisation.

In this fraught panorama, ideologies and party programmes still count for something. The established parties are increasingly perceived as a uniform block, with the far right being the alternative, but the truth is that the social democratic, social liberal, centrist, liberal and conservative parties of yore have radically different solutions and proposals on how to navigate these issues. In the EU elections, there is plenty to choose from, according to one’s ideological position. Yet, this increasingly goes under the radar, as the far right grows louder and the established parties grow timid.

The Strategy of the Far Right

In this light, the obsession with far right parties seems particularly ill-advised, and at times, positively morbid. The coming EU elections are described by some (including S&D’s leading candidate, Frans Timmermans) as ‘a battle for the soul of Europe’, and while that is certainly true, it is on existential threats like climate change or a world recession, that the EU’s soul will be won or lost.

The far right holds no answers for any of these delicate policy points. It is, however, benefiting from the bizarre soul-searching that its rise has instigated among Europeans, trying to figure out where the origin of the ‘populist’ wave are to be found. Inevitably, the answers that are usually offered tend to coincide with the far right’s own narrative of itself and its success. Uncontrollable migration, out-of-touch elites, political correctness gone too far; everywhere in the EU, the storytelling of the far right is taken completely at face value. This is especially puzzling, when the origins of the phenomenon are actually remarkably simple, and have nothing to do with LGBT rights or wealthy elites, of which far right leaders are usually members themselves.

The current, often self-styled “populist” parties are a modern declination of the same far right ideologies that have been with us for the majority of contemporary history. Indeed, their stated priorities are sometimes so identical to those of the past as to give an uncanny sense of deja-vu. The governing Italian coalition’s strong criticism of large shopping malls in favour of traditional, family-led boutique shops follows word for word the same political arguments about global capitalism that framed much of the economic debate in Germany, France, and others during the first three decades of the 20th Century.

Even in their modern edition, these parties have roots that are much older than the refugee crisis of 2015. From their attempts to mix fascism with popular culture, to the challenge they swore to lead against the global constellation that emerged after the Cold War, these parties have been at it for a long time. In 1999, electoral results in Austria triggered panic and fear across the Union. It was in 2002, when the Great Recession was still far into the future, that the Le Pen dynasty shocked Europe by getting through to the second ballot of the French presidential elections. At around the same time, the Bush administration was increasingly turning to economic nationalism, trade protectionism, and making sympathetic noises to the far right.

Globalised Anti-Globalists?

This leads us to an important point: the phenomenon isn’t specific or native to the EU. From Brazil to the Philippines, places which have not experienced the refugee crisis of 2015, the far right has already redefined the political landscape. The Republican Party in the United States is the most poignant example: the far right turn of the GOP did not begin with Trump, and in fact it didn’t even begin with the Tea Party, it began with the Neo-conservatives, Newt Gingrich, and Dick Cheney, as far back as the early 1990s. It began with the United States increasingly seeing its own creation, the U.N., as a limit to its ability to act.

President of the European Council Donald Tusk and NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg sign a joint EU-NATO declaration. Both sides of the Atlantic are experiencing similar challenges to the liberal order they helped establish.

As much as the refugee crisis of 2015 is a popular talking point for the European far right, therefore, it’s not the ultimate root of its success. The far right has skillfully played on diffused fears to create a warped perception of immigration, but the transition was already underway. And what really propelled it into high gear was the Great Recession, which provided these parties with the big break they had been looking for, and it’s on the back of that event that they will try to score further gains in the coming EU elections.

Wondering about the growth of illiberalism can reveal a lot about the Western world after the Great Recession, but it plays a marginal role at best in defining the coming battle for the soul of Europe. Explaining the success of the far right with the refugee crisis, when just over a decade ago the world suffered the largest economic meltdown in living memory, is looking at the finger rather than the moon. And as the effect of the economic meltdown interlocks with climate change, trade wars, and the spectacular return of great power competition to the realm of foreign policy, the cumulative effect of these problems might well exceed our ability to tackle them.

Fear Itself

As Otto von Bismarck once famously put it, statesmanship is the art of steering the ship of State down the stream of time. Based on everything listed so far, one might conclude that we’re about to enter some very stormy waters. This, however, should not deprive us of our optimism.

It was in similarly dark circumstances that Franklin Delano Roosevelt was elected president in the United States, and that historical moment contains a very powerful, and very relevant lesson. With totalitarianism on the rise everywhere in the world, the economy devastated to such a level that no one could take its recovery for granted, feverish social tensions and a world war on the horizon, it would have been easy for Roosevelt to retrench. He chose, instead, to deliver a positive message: the only thing we need to fear is fear itself. By forging ahead together through these difficult times, we can make something good out of it. History shows that they did.

The stakes in the EU elections are similarly high, and yet the European Union lacks a Roosevelt – or indeed any kind of positive agenda. Both the media and the established parties fail to talk about the existential challenges we face in a way meant for public consumption. More importantly, the latters fail to stand up for themselves and their own vision on how to navigate the crisis.

These are the issues that should be at the forefront of our minds, when we head to the poll and cast our vote or when we push others to do the same. This point, however, will never get across to voters unless the mainstream parties make a conscious effort of rectifying their inexcusable vacuum of communication. Only by presenting their positive agenda can they once more frame EU elections, and curb the increasingly self-referential obsession with the far right. The future of the European Union depends on it.