On this day in 216 B.C. : the battle of Cannae

On 2nd August 216 B.C., Hannibal won his greatest victory north of Cannae, a small city on top of a hill in southern Italy. When the day ended, his numerically inferior mercenaries had surrounded and slaughtered a majority of the largest army Rome had ever produced. Cannae would become the disaster that all other defeats would be measured against. The defeat at Cannae was never surpassed, and matched only a couple of times, during the entirety of Rome’s existence. However, the battle influenced more than just the Romans and has loomed large in military minds ever since.

The commander of the U.N. forces during the Gulf War (the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait), Norman Schwartzkopf, supposedly studied Hannibal and especially the Battle of Cannae in preparation for his own short, but devastating, campaign. Alfred Graf von Schlieffen, the inventor of the planned invasion of France during WW1, was obsessed with Cannae and attempted to achieve a similarly total victory within the frames of his battle plan.

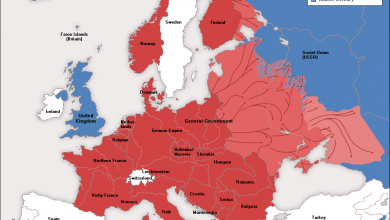

As the Desert Fox, Erwin Rommel, was driving the British back to Tobruk in 1941, he wrote in his diary that “a new Cannae is in the making”. A year later, during the Battle of Stalingrad 1942, the commander of the 6th Panzerdivision boasted in a report about a day of successful fighting around a little village called Pachlebin, calling it the “Cannae at Pachlebin”.

The Roman Senate decided in 216 B.C. that they had had enough. One of the two consuls and three of the four praetors had all been consuls before. For the first time, each consul was entrusted with an army twice the size as usual, and they were expected to fight together as one. This almost insanely huge army was the largest ever fielded by Rome up to that point, comprising eight legions of 5000 men each, along with the auxiliary troops. More ominously, this was but a part of a far larger Roman mobilization, which Hannibal could not match.

Disregarding the forces already in place in Iberia and Sicily, two legions were sent north to deal with the tribes in Gallia Cisalpina, by then in open revolt. The two consuls put in charge of the largest Roman army were Gaius Terentius Varro, and Lucius Aemilius Paullus. Paullus was the grandfather of Scipio Aemilianus (the destroyer of Carthage) and therefore he received abundant praise by both Polybius and later historians.

Paullus died during the Battle of Cannae, but unlike his fellow consul, he came from a wealthy family who was more than able to protect his legacy during the following years. Varro not only survived but was also from a new noble family and was, therefore, an easy scapegoat. The historian Livy refers to Varro as a demagogue (similar to what was said about Flaminius, the consul who refused to perform rituals before getting decisively defeated at the Battle of Lake Trasimene), and mentions further that the father of Varro was a butcher, a simple insult in Roman politics, and as such should not be taken seriously.

The Roman army consisted of around 80,000 infantry and 6000 cavalries, facing Hannibal and his 40,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalries. Morale was soaring: the delaying actions of Fabius gave Rome the time to recover and keep mobilizing new armies. Further, Hannibal’s pillaging of the Italian countryside mostly occurred not on Roman soil, but on land belonging to allied cities of Rome: as a consequence, the allied soldiers were particularly motivated.

At the beginning of the campaign season in 216, Hannibal was still at his winter quarters at Gerunium in Apulia, carefully observed by Roman troops. When the time came to bring in the harvest, Hannibal left Gerunium, shadowed by the Romans who repeatedly sent notes to the Senate, urging them for orders. Hannibal hurried across the land until he reached the ruined fort of Cannae, that now served as a Roman supply post.

As the main Roman army drew closer, they advanced carefully, not wanting to repeat the mistake of Flaminius, who chose not to scout the terrain and because of that got caught in an ambush at Lake Trasimene. It would appear that they travelled along the plain of the coast, possibly to avoid positions good for ambushes. As they saw the enemy army, they made camp, approximately 10 kilometres away.

The consuls took turn taking command of the army, and Paullus is said to have told Varro not to advance against Hannibal, as the flat terrain would give the Carthaginian numerically superior cavalry a distinct advantage. Varro did not heed this warning.

As the Romans marched forward, they were attacked by Hannibals’ cavalry and light infantry, and panic spread amongst them until they were able to reorganize and drive the Carthaginians back. The Roman Velites (skirmishers) and cavalry fought with legions as close support, giving them an edge over the enemy. The skirmishes continued until dusk, and it is doubtful that the Romans managed to advance many kilometres until they were forced to make camp. The next day, the advance was continued by Paullus who moved the army until they were just a few kilometres away from Hannibal.

Polybius claims that Paullus was still uneasy about the terrain, but then decided they were too close to Hannibal to safely withdraw. It is highly likely that Polybius was trying to shift the blame of the defeat from Paullus to Varro, but the reality was that they were in fact too close. Retreating across the open plains would have left them incredibly vulnerable, and in any case, a retreat at that time would have devastatingly demoralizing effects on the troops.

The Romans were under pressure to engage Hannibal in combat, as their large army would be very hard to supply, and if they waited too long they would be forced to divide up their forces in order to keep all soldiers and horses fed. Hannibal faced similar difficulties, and Livy claims that some of the Carthaginian mercenaries, especially the Iberian troops, were thinking of desertion. Furthermore, Livy says that Hannibal planned to flee to Gaul along with his cavalry, but this act of desperation is likely just a figment of Livy’s imagination, to highlight the folly of abandoning Fabius’ delaying tactics.

For several days, the two armies sat idly by, staring at each other, and fighting small skirmishes. Both sides were becoming desperate for a battle, but neither side wished to move too soon. Finally, on 2 August, Varro raised the red “vexillum” (flag-like object used as a military standard) signalling that the time for battle had arrived.

-

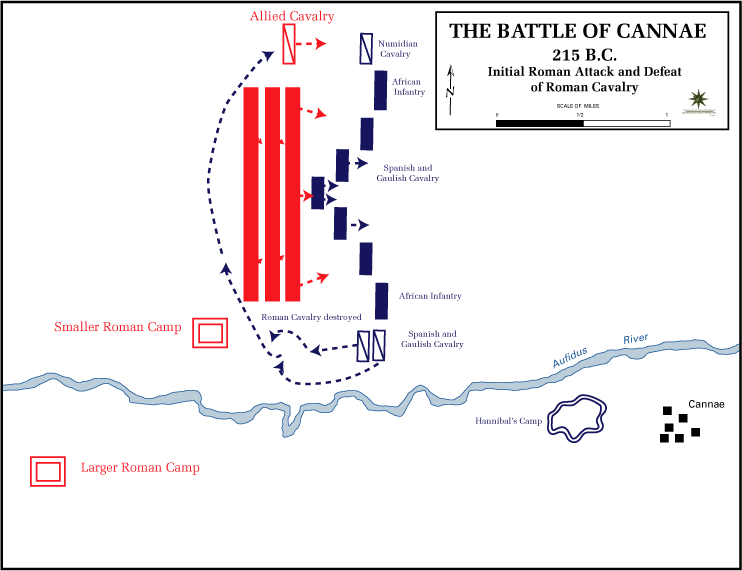

Initial deployment and Roman attack (in red)

The Roman army positioned itself so that its right flank was facing the banks of the River Aufidus. The centre was held by the strongest component, the heavy infantry of the legions and the auxiliary heavy infantry. The Romans decided to make their formations much tighter than before, mainly because the terrain available was narrow, and also to increase the pressure built up by constantly moving soldiers slowly pressing forward.

The Roman battle plan was simple and built upon lessons learned from the previous battles. At Ticinus and Trebia, the Roman cavalry had been defeated by the superior Carthaginian counterpart, allowing the Carthaginians to flank the Roman infantry. Even so, the Roman infantry broke through the enemy centre at the Battle of Trebia, and even during the chaos of the Battle of Lake Trasimene, the vanguard managed to punch through the enemy lines. The reinforced Roman centre should now be able to crush the Carthaginian centre, and the cavalry only had one goal: to protect the flanks until the infantry had accomplished their mission. The terrain made it difficult for flanking maneuvres by cavalry and this spoke in favour of the Romans.

Hannibal had been forced into battle at a terrain that was a huge disadvantage for him, and he had no elephants remaining. Neither did he have any chance to ambush his enemy, and now, the sheer number of Roman soldiers would finally crush this upstart Carthaginian. The Romans drove in hard, using their superior infantry to best advantage. They had their Velites fall back and ploughed into their foe with their heavy infantry. The crescent of Celtic and Iberian swordsmen buckled and retreated. To the Romans, this appeared to be due to their powerful drive into the opponents’ lines. In fact, the troops had been told to retreat. The Roman infantry kept on driving into the Carthaginian lines.

-

Destruction of the Roman army

Forcing them back, they still felt confident that they were winning. But as they shunted forward and the opponent withdrew, the light infantry on the Carthaginian side, though itself staying stationary as it wasn’t withdrawing, began to emerge on the Roman flanks. Worse still, on the wings, Hannibal’s Celtic and Iberian cavalry was driving the Roman cavalry back. Combined with the advance of the Roman infantry this meant that there emerged a gaping breach in the Roman line. A large body of cavalry now separated from the Carthaginian left wing and charged across the field of battle to the right wing, where it fell into the rear of the cavalry of the Roman allies.

The Carthaginian cavalry effectively defeated the Roman cavalry, and the Carthaginian infantry did the same with the Roman legions. The Roman infantry had continued to drive forward and had driven itself into an alley formed by the light Carthaginian infantry stationed at the sides. Shielded by these Carthaginian troops, their comrades who had stayed at the rear could now swing around and come in behind the Roman army. The doomed Roman legions were encircled and being attacked from all sides. In effect, the Roman infantry had been defeated by the opposing infantry, although the returning Carthaginian cavalry helped further accelerate their victory.

The Roman army had defeated itself. It had solely relied on the superiority of its legionaries, having lined them up and told them to advance. No use had been made of the superior numbers, other than to simply add more ranks onto the back of the advancing columns. As the Carthaginian units manoeuvered, nothing was done to counter their actions.

One simply did what one had always done – advance. Such ignorance was most likely born from the fact that the battles with Hannibal were the largest contests Rome had ever fought by that time. Despite their earlier dealings with king Pyrrhus, they most likely had not gathered enough experience yet in such matters to be able to cope with such huge a challenge. They would soon put these lessons to good use for further mobilizations and spectacular comebacks.