The Kosovo Liberation Army: From Guerrilla to Politics

On the 24th of June 2020, Hashim Thaçi, President of the Kosovo Republic, was charged by Kosovo’s Specialist Chamber, one court of the Hague, for ‘war crimes and crimes against humanity’ during the Kosovo War (1998-1999). This announcement came as a shock in the Balkan Peninsula, especially in Kosovo where such subjects remain somewhat taboo.

Thaçi resigned in early November and is now facing trial. But he isn’t the only one who has been called to The Hague recently. Former Kosovar Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj was called as well in 2019, triggering the early legislative elections of October 2019. Both men were prominent members of the Kosovo Liberation Army (UÇK): a former paramilitary unit, a prominent figure of Kosovar independentism, and one of the main actors of the last war in the Balkans.

Kosovo within the Socialist Federation

Kosovo has been attached to Serbia for centuries and a prominent place of Serbian culture and history, which grew on a territory populated by Albanians that settled there in early Middle Ages. When the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRJ) was formed, Josip Broz Tito and the newly formed Communist government separated Serbia in three parts, in an attempt to weaken Serbia’s influence on the country.

These were Serbia itself and two autonomous regions. Vojvodina in the north of the country, because of the Hungarian minority, and Kosovo in the south because of the Albanian population. Vojvodina had more devolved powers, still considering that this devolution took place under a communist, autocratic state. While Kosovo remained more directly controlled by Belgrade between 1945 and 1963, it received the exact same powers as Vojvodina in 1963.

These concessions were granted by the SFRJ to weaken Serbia’s influence within the communist Federal State. In Kosovo’s case, these were also used to appease Albanian nationalism. One of the main objectives of the Yugoslav government was, indeed, to suppress any form of nationalism in any of the Republics and by extension, autonomous provinces.

When Tito died in 1980, an economic crisis fell on the country and nationalism started to rise again. While the main focus was indeed Serbia and Croatia, nationalism and Albanian irredentism also started to be noticed. The Kosovar and Albanian diaspora that settled in Western Europe strongly supported the movements that emerged in Kosovo, and supported movements that would later merge to form the UÇK.

The Republic of Kosova

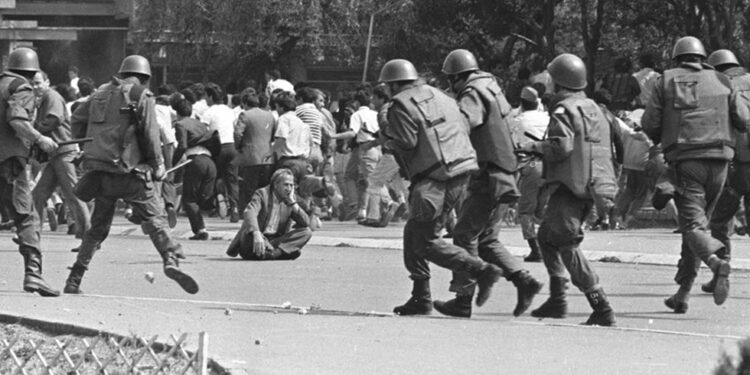

In March of 1981, the first significant protests in Kosovo erupted, marking the beginning of the Yugoslav collapse. Students demonstrated for more autonomy and more liberties, whilst the federal and Serbian authorities answered by sending in troops. It ended with several casualties on both sides, thousands of arrests, and the massive sacking of people from the Kosovar branch of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. The protesters’ ‘nationalism’ was then considered ‘unacceptable’. Several thousands of Serbs emigrated to Serbia from Kosovo, fearing retaliation.

Fast-forwarding to 1989, on the 600th anniversary of the Kosovo Polje battle, the Serbian government revoked Kosovo’s autonomous powers that were granted through the history of the SFRJ. Kosovo returned to its 1945 status, basically under the tutelage of Belgrade. It was a part of a more global movement called “Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution” in which Milošević arrested and replaced local leaders in Vojvodina and Kosovo to ensure the support of the autonomous regions to his regime for the upcoming wars. 1989 also was the year where the LDK (Lidhja Demokratike e Kosovës, Democratic League of Kosovo) was founded.

Across 1990, the Communist regime officially collapsed and the Serbian government kept suppressing Albanians’ rights. Kosovar officials attempted to maintain neutrality during the war with Bosnia and Croatia, while many Albanian soldiers within the Yugoslav Army deserted. In July 1990, the Republic of Kosova was formed and would self-proclaim its independence in 1991, immediately and solely recognized by Albania. With the escalation of the tensions, Serbian authorities revoked any autonomy that Kosovo had left, at least legally. The Republic of Kosova indeed went on developing its own underground institutions.

UÇK Rising and the Kosovo War

The UÇK would become more and more important in the early Nineties, with more volunteers joining due to the frustration over how Belgrade was treating the Albanian population. Most of their fighters were trained in underground training camps under the patronage of Adem Jashari, one of the leaders of the UÇK.

After the Dayton Peace Agreements of 1995, the situation in Kosovo started progressively worsening. There were often generalized clashes between Serbian forces and the UÇK, the latter targeting Serbian military forces, police, and civilians. Belgrade answered by sending more troops up until 1997, which did nothing but allow the tensions to escalate even more.

The LDK, which as at the time the biggest party in Kosovo (though officially banned by Federal authorities) was highly critical of the UÇK actions, which targeted civilians, and attempted de-escalation. Due to Belgrade’s violent answer, more and more Kosovars saw armed guerrilla as the only option to resist the Serbian forces. This would drive a wedge between the LDK and the UÇK. Indeed, during those times, several spokespersons of the Party or militants disappeared or were killed. The suspicion is that UÇK attempted to eliminate people that would have been classified as ‘traitors’.

By February of 1998, Yugoslav authorities had started engaging in a full-on war in Kosovo by sending the actual army and divisions, not only law enforcement, to crush the insurgency once and for all. The Yugoslavian troops were well equipped but lacked the full knowledge of the terrain the UÇK had. Later, in March 1998, the UN Security Council Resolution n°1160 imposed an embargo upon the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia to force Belgrade to cease the repression. It also qualified the UÇK as a terrorist organization. The US envoy to the Balkan, Robert Gelbard, also used these same words to describe it, although it was never the official position of the US government.

During the following months, Kosovo was plagued with war and massacres coming from both sides. Federal troops’ advancement forced the mass relocation of Kosovar civilians. After the failure of Rambouillet Conference negotiations in March, NATO bombings started against various targets in Yugoslavia and Kosovo. The relocation and killing of Kosovar civilians became more and more widespread after that. Shelling, destruction of mosques, houses and entire villages were to be seen all across Kosovo. The war ended with more than a million of displaced Kosovars.

The UÇK answered Yugoslav actions by abducting and killing Serbian civilians all around Kosovo, as well as forcible relocations. The UÇK opened up prison camps and used their prisoners for forced labour, often under the threat of summary executions. Answering the Yugoslav army’s destruction of mosques, the UÇK went up to destroy or damage orthodox churches and monasteries. It is also important to note that the UÇK also intensified its crackdown against Kosovars opposing their violent actions, killing and abducting some of their critics as well.

According to the latest research, the Kosovo war ended with the death of approximately 15.000 civilians. 10.000 of those were Albanians and approximatively 2.200 were Serbs. Millions of civilians ended up homeless or displaced out of their house.

Post-war Kosovo and “Commander Politics”

Immediately after the end of the war in June 1999, while the Yugoslav people were turning against the dictator and the opposition was gaining more and more traction, UÇK guerrilla fighters, despite the efforts of KFOR and UN troops, started to harass Serbian civilians in Kosovo. Beatings, assassination, burning of homes and churches became widespread, as well as pressures on Serbian and Roma communities. Everything was fair game to force them to leave Kosovo.

It is estimated that up to 200.000 Serbs were driven out of their homes by UÇK fighters, in addition to the 90.000 Serbs that had fled during the war. Along with them went several thousands of hundreds of Roma people, although their precise number is unknown.

Kosovo remained de facto under Serbian sovereignty according to international law, but Belgrade virtually lost all control on the province. After years of tensions with Belgrade and poor progress being made, Kosovo unilaterally declared its independence on the 17th of February 2008.

The same year, Carla del Ponte, Chief Prosecutor of the ICTY, famous for chasing Serbian war criminals, made shocking revelations. In The Hunt, a book that came out in 2008, she exposed how several hundreds of Serbian civilians had been abducted by the UÇK and had their organs stolen to be smuggled. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe immediately started an investigation, gathering testimonies. If del Ponte was previously praised in Kosovo for her fight against Serbian criminals, her determination to chase down Kosovar criminals afterwards turned the public opinion against her.

Kosovo has been a battleground between the PDK (Democratic Party of Kosovo, the political wing of the UÇK), the AAK (Alliance for the Future of Kosovo, the party of Ramush Haradinaj) and the LDK since its independence. Several scandals, especially in regard to corruption, have undermined the progress that Kosovo could make. Reports by the European Union, as well as other foreign observers, are all denouncing this situation.

The shady policies led by former UÇK members that went into politics have been ironically labelled ‘Commander Politics’ by part of the country. Last year’s election constituted a break in tradition, resulting in Vetevëndojse gaining the most seats – though Albin Kurti’s government didn’t last long.

Trialling the UÇK

The pressure imposed by the international community led to the opening of Kosovo’s Specialist Chamber in 2016. This was something that Thaçi originally supported but which has sparked angry reactions within Kosovo, both by political parties and the population. There, criticizing the UÇK can be dangerous in some circles, as can be seen in the case of Shkelzen Gashin. A journalist and political analyst, she received death threats in April 2020 after stating that the UÇK committed war crimes.

The crimes committed are, in fact, not something broadly talked about in Kosovo. They’re often relativised, since they were answering the violence of the Serbian forces. The fact that the UÇK crimes are dismissed so summarily is worrying: the main goal of several former high ranking members of the UÇK was to create an ‘ethnically pure’ Kosovo, without any other communities such as the Serbs, Roma people, Kosovar Egyptians and so on.

Thaçi and Haradinaj facing trial may force Kosovo to have an internal debate about the UÇK, its actions, and the role it played in the country’s politics. Minus the LDK, which historically opposed the UÇK actions, nearly all major parties have at least one top figure indicted by the Kosovo Specialist Chamber for past crimes during the war.

The rhetoric of the UÇK shouldn’t be one used in mainstream politics, as it is inherently violent against some of the communities populating Kosovo. All criminals have to be brought relentlessly to justice, and Kosovars can’t an exception to this rule. Only with all the criminals out of important positions, whether it is in Serbia or in Kosovo, can the healing process be truly complete.