On October 26, the remains of Franco were exhumed from the mausoleum in the Valley of the Fallen near Madrid, and moved to the El Prado cemetery in a family tomb. The disinterment and reburial – the corpse was flown by helicopter between the two sites – occurred without incident. All media coverage was forbidden on the day itself, though the event was heavily covered in the lead-up.

The exhumation and reburial followed a decision by the Spanish Supreme Court a month earlier to allow the government to remove Franco’s remains. In a filing before the court Franco’s family rejected the exhuming but also expressed a preference in the case of reburial, the Almudena Roman Catholic Cathedral, adjacent to the Royal Palace in central Madrid. Reburial would then occur alongside his daughter, rather than in the more modest El Prado cemetery. The government wished to exhume the body and avoid a reburial site that could lend itself to promoting a cult of Francisco Franco.

The court ruled in favor of the government on both counts. The reburial was the culmination of a promise made by the governing Socialist Party in 2018. If this were Italy or even Germany and the remains of Mussolini or Hitler reburied, a national crisis would occur. Spain remains eerily quiet, troubled more by the judiciary’s reaction to Catalan separatists.

Francisco Franco and his legacy

Franco’s reburial comes in a complex political context. Spain was the last country in Europe to harbor a popular extreme right wing movement since the fall of Franco and Portugal’s Salazar in the mid 1970’s. The exhumation was a dramatic background to the latest elections, although over shadowed by the events in Catalonia. No one is at all sure either in what way the feelings about the exhumation may have influenced the vote, if at all.

It was not until the regional elections of last year, in December of 2018 in Andalusia, that a far right wing party, Vox, penetrated the Spanish political system again, gaining 12 seats out of 109 in Andalusia. In the national elections of May 2019 the party continued its success gaining 24 seats, or 7% of the Spanish Parliament’s 350 seats. In the European Parliamentary election of 2019 Vox reached 6% of the Spanish vote, gaining 3 seats out of a total of 54. Though founded in 2013, and presenting candidates in the election of 2014, this was the first time Vox or any far right wing party had electoral success in Spain since the end of Franco’s regime. This does not mean that there was no far right wing sentiment after the experience of Franco, but simply that the country was too shocked by the experience of the Falangist dictatorship to allow it national expression.

On March 28, 1939, some eighty years ago, the duly elected Spanish Republican government and its allies suffered final defeat on the outskirts of Madrid. This marked the end of a three year old civil war, won by Franco’s Falangists and their Nazi and Italian Fascist allies. So began thirty-six years of Falangist one-party rule in Spain. Franco’s rule was marked by score-settling, imprisonment and torture for many who had defended the properly elected Republican government. With Franco’s death in 1975 his regime came to an end. The Spanish people are still trying to come to grips with the civil war which tore the country apart.

Today Spanish politicians are still arguing over the now accomplished removal of Franco’s body from the enormous war memorial and mausoleum honoring the fallen on the outskirts of Madrid. The decision was taken in August 2018 by the Socialist government. The Vatican, though hardly all Spanish Catholics and clergy, weighed in affirmatively, backing the government’s decision even though Franco was a staunch Catholic, supported by the Spanish Catholic Church. A complex pas de deux between the local Bishop, family and government as to whether he could be reburied in the Cathedral in Madrid, next to his daughter in a family crypt, was finally resolved by the Supreme Court, much to the relief of the government.

Meanwhile the remains of captive republicans who provided the labor to build the memorial are already being removed. Families are lobbying for the right to exhume more bodies, those of their loved ones deceased in the civil war and buried elsewhere, often scattered in common graves around Spain. They want to give them proper burial, which had long been forbidden in a desire not to reopen the old wounds of war. The dead numbered in the hundred thousands, but travel around Spain and you would see nothing of all these emotions seething underneath the surface. Some things take a long time to re-emerge.

In 1977, a few years after Franco died, Spain passed an amnesty law referred to as The Pact of Forgetting meant to ease the transition to democracy. It was temporarily effective in burying passions and recriminations from the era, but also legitimate demands for justice, for example those stemming from torture. It has since been challenged by Spanish judges but upheld by the Supreme Court, all while the UN has urged Spain to repeal it, affirming that crimes against humanity cannot be amnestied.

In Argentina a judge is investigating under international law crimes committed under Franco. Jurisdiction is yet to be determined. In 2004 the Socialist government succeeded in passing The Memory Law which invalidated all Franquist laws and banned Franquist symbols. Some argued it did not go far enough as immunity remained. A socialist-initiated government office exhuming and reburying victims was closed when the conservatives took power.

The return of Eternal Fascism

It would not be saying too much to say that fascism is the tune that has played the piper, at least the contre-temps, in the 20th and 21st centuries. Surprising, but only if one is too literal, as the term “fascism” is not well liked nor understood. But look out objectively and you will be sure to recognize fascism’s signature throughout contemporary history, since fascism’s inception ninety-seven years ago in 1922 with Mussolini’s march on Rome, and continuing on today.

In a remarkable essay titled Eternal Fascism, by Umberto Eco, an Italian scholar took this historical knowledge and showed the common threads in all of these movements. Eco concluded that fascism was a form of political philosophy that has reared its ugly head repeatedly in our times, even when it has not adopted the name. It is a type of sickness or behavior that recurs in different forms, but with a remarkably similar typology.

Today we are again looking at movements that claim their allegiance to “fascist principles”, rally around decades-old fascist symbols and revere the fascist founders. The widespread and enduring importance of fascism allows us to see the Spanish civil war in a new light. Franco’s dictatorship, which fractured Spanish society, and to some extent still does, is not an anomaly in the past history of the West – one which we can leave behind safely to be forgotten and remembered only by specialist historians – but rather a key event in the consciousness of the West. A moment that the West not been successful in forgetting.

Tales from the Spanish Civil War

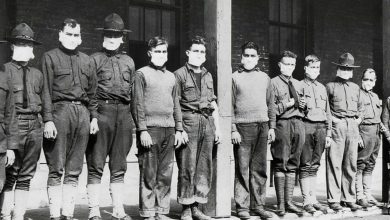

Tucked into the pre-war period and the Great Depression from 1936-1939, the Spanish civil war was a living hell for the country’s citizens. Into this hell rallied International Brigades bringing mostly young recruits from among artists, elites and working class volunteers all around Europe, the United States, Canada and Australia, to as far away as China – joining with communists, socialists, anarchists, simple workers and peasants to seek a better life and try to protect democracy.

What was the attraction of assisting in this slaughter, risking one’s life? The story is complicated, much more than a battle between fascists led by Franco and aided by Hitler and Mussolini and anti-fascists aided by the Soviet Union, communists, anarchists and Inter-nationalists. Why didn’t the West, soon to fight Hitler himself, come to the aid of Spain’s democratically elected Republic? Why has this failure been covered up by years of silence while the much less important one, the concessions to Hitler at the Munich Conference – though it was in Hitler’s own back yard and much more difficult to affect than the situation in Spain, – is described as a failure to this day? Hitler’s annexation of the Sudetenland, Czechoslovakian territory with a largely German population, agreed to at Munich, is seen as appeasement that encouraged further aggression. Giving Hitler, Mussolini and Franco free reign to destroy a democratically elected government in Spain, only a nautical hour from Britain and a mountainous traverse from France, strangely, is not.

This is where the bourgeoisie consciousness of the West begins to fray, trying to hide from scrutiny and self-scrutiny. It has done so successfully, except for the resurgence of a problem that has never really gone away. You see, while the Republic’s government was democratically elected, it was also socialist and reformist – not something the major land, industrial or Church interests in Spain and the West wanted to deal with, much less accept. It was also supported by communists and aided by the Soviet Union, which brought into play major power politics and bitter ideological rivalry.

This was not the first or last time that the West neglected or actively undermined a democratically elected government of the left, but it was another with dramatic consequences. Mossedeq in Iran was similarly impaired, and the consequences are being felt to this day. The assassination of Lumumba resulted in civil war in Congo. Chile suffered a brutal dictatorship after a coup engineered by the CIA against the elected Socialist government of Allende. The refusal to recognize the Muslim parties elected in Algeria in a democratic election, or Hamas in Gaza are some additional examples of elected governments which have not been to the West’s taste and subsequently not diplomatically recognized by it.

Non-democratic, but populist reform governments with widespread support, are also targets of Western repression, when they lean to the left. The coup d’etat against the Socialist reform government of Sankara in Burkina Faso, although coming to power in a military coup itself, replacing a monarchy, set off civil wars throughout West Africa. Castro’s Cuba underwent world wide isolation from the West and their allies for well over a half-century, which is now being renewed by the U.S. after earlier detente. A similar fate is being experienced by the Venezuelans. The result of undermining the popular will has usually been bad, in Franco’s Spain predictably so.

The Spanish Republic before the War

What makes Spanish example important in our history of fascism is the scale of the ensuing slaughter and the destruction of the hope that the Republic represented. For on quite a number of issues the Republic breathed new life into Spain, which was why it inspired so much international support from individuals, artists, intellectuals, and simple working and middle class people, if not from their governments.

The Republic was years ahead of anywhere else on women’s, workers, gay, democratic and economic rights, and many of its reforms have endured to be copied elsewhere – though often without the fullness and pride of ownership of the Spanish republicans. Rather similar reforms in Western societies have come about grudgingly and piecemeal, often leaving class division and antagonism as bad as they were before, or displacing these antagonisms on the new groups affirming these rights. LGBT people, women, workers, the poor and immigrants, have often gained rights in Western societies only to remain marginal, and occasionally still subject to scorn.

The main argument against the Republic, at least the most rational one, was that the republicans wanted to go too far and too fast. This was certainly a risk with communists, anarchists and socialists all vying for power and pushing in different directions. But by snuffing out and literally killing off any remaining Republican sympathizers, rather than letting their internal struggles run their course, Franco set back Spanish society by half a century – the scars will remain for much longer than that.

Children of socialist and communist families were taken from their parents to be raised by “good” Catholic families. These children have sometimes just begun to realize their real identities. Fathers and brothers were taken away to be assassinated, their remains buried in secret graves. Families are just beginning to recover the “missing” remains.

For their part, republicans, although not officially the Republic, assassinated many priests and religious friars, some of whom were certainly innocent of the machinations of the Church hierarchy, allied with Franco. The divide between Catholic and atheist Spain is, as a result, wider than ever. Recently, when the dual nationality (British-Spanish) author Giles Tremlett was researching a book on the consequences of the conflict, Ghosts of Spain, many Spaniards refused to accompany him inside a Catholic church in the course of his research, preferring to wait for him outside because of their enduring hatred of the institution. Republican combatants were hardly choir boys and girls either. Communists were doctrinaire and undemocratic, revenge and ideological killings by partisans were not uncommon. It was civil war with all that implies.

And yet, until very recently in Spain, all this had been swept away in silence, not taught, books and histories of the period banned, buried in economic growth and hopes for the future, but unfortunately not going away. And in the rest of the West, Spain was treated as an irrelevant footnote to history made elsewhere. Yet for 44 years since Spain was practically the only country in Europe without a popular extreme right party. The exhumation and regional passions seem to have awakened the dead.